-->

As I hear more and more of the

negative criticisms of rap, new ideas are starting to occur to me. One of the

most interesting is that, perhaps, people who don’t like rap music simply don’t

know how to listen to it. This might

be a strange idea to some, to have to learn how to listen to something. Yes,

most of us can hear things – but how do we really listen to something, by which

I mean the music in its proper context, a context that reveals just as much

about the music as the music itself does. I would posit that this idea is not

as farfetched as it might first seem. Yes, when we read a book, there is the

story on the page in front of us that we enjoy. But if we are aware of the

greater narrative of the book, such as themes and symbols, inevitably our

enjoyment of the experience deepens. Such a metaphor can be applied to music.

This

whole phenomenon has struck me in a certain scientific sense. (What follows is

a gross oversimplification, and might even be an outright misrepresentation of

the scientific method – but such is the result when you have a humanities

student trying to explain it.) I think of it in terms of a scientific

experiment, where we need to isolate variables and observe their response. We

have some variables that we want to measure, and we can only do so accurately

if we are able to isolate them. Roughly, what I have suggested in the previous

paragraph is that there is a musical meaning to rap that is able to be divorced

from its textual meaning while still having an internally consistent meaning

(note, however, that the two can never be studied completely in isolation from

each other, as we shall see.) But how could we ever possibly isolate these,

respectively, musical and textual variables? Certainly, there is no rap (here

referring to both the musical and textual – that is, the lyrics – elements of

rap) that has a textual meaning but no music, and there is no rap that has a

musical meaning but makes no textual sense…or is there?

Enter

what I currently consider THE most interesting (not necessarily in a positive

sense) rap song of all time, Eminem’s “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em”, produced by Dr.

Dre, from the album “Relapse”, released in 2009. This was Eminem’s first album

in 5 years, since his 2004 “Encore”, a hiatus due to his writer’s block and an

addiction to prescription sleeping medication. This song is located at an

exceptional instance of an artist who is in the unique stance of knowing that

his place in the pantheon of all-time-rap greats has already been secured, and

he is still in his prime writing years (He was about 36 at the time). He is

making a comeback – people haven’t heard from him in 5 years. How is he

supposed to follow up “Encore”? “The Marshall Mathers LP”? “The Slim Shady LP”?

“The Eminem Show”? The man has won Grammys, popular and critical acclaim,

worked with the greatest producers of all time, and yet he still has to prove

himself because of his hiatus. He hasn’t forgotten how to rap – in stark

contrast to other legends in similar but certainly not the same circumstance,

like Jay-Z or Lil Wayne, he hasn’t fallen off. But he’s just had about 50% of

his lyrical material considered “off-limits” to him: he is now trying to go

clean, so that means no rapping about weed, shrooms, vicodin, oxycodin, all of

that stuff (Just check out his song “Drug Ballad” – but maybe the title lets

you know all you need to know.) So he can still rap – but what the hell is he

supposed to write about? This is the central tension, certainly palpable and

almost tangible, in this song.

The

answer is, figuratively, “nothing.” Eminem manages to rap over 55 bars without

actually saying anything. What’s more is, this goes beyond the normal amount of

nonsense that the listener naturally allows when listening to rap, simply

because, as I believe, it’s predominantly a musical phenomenon, not a textual

(or even poetic, in the general sense) phenomenon. Let’s take a popular example

today:

In Bobby Ray’s “Ray Bans”, he raps

“My whole team getting green, and I ain’t talking about pottery.” Now, not all

pottery is green. I think when he says pottery he really is referring to

plants, most of which are green. Still, the connection is thin. But Eminem goes

beyond this point.

Nothing he says in

this song really has any real connection to anything outside of his world.

Let’s just say you don’t come away from the song pondering in what sense,

exactly, Eminem is “like Chef Boyardee in this bitch.” Or what metaphoric

meaning he is reaching for when he describes himself as “Captain America on

ferris wheels.” And don’t overthink it. Okay, yes, rap is a genre built on

reference and allusion – but these tools lose their power when no one at all

gets them, even if they are references at all (which they aren’t, here.) This

kind of shit is all over the song. What the fuck is “bumbaclot?” When Eminem

tells me that I think I’m Tom Sawyer, does he really think I’m a 19th

century juvenile dilenquent living along the Mississippi? When he tells me I

should “Get some R&R and marinate in some marinara,” what really should I

do? And these are simply the most egregious of the violations of not just

commonsense, but sense.

The

saddest part of this, though, is when Eminem reaches for lifesavers in the form

of themes and ideas he used to rap about all the time. For instance, even if

you haven’t heard Eminem’s music, you know that his relationship with his mom

has been less than perfect. His earlier references to this subject come across

as tortured and agonized when examined, such as his raps “99% of my life I was

lied to / I just found out my mom does more dope than I do” in “My Name Is”, or

‘When I was just a little baby boy, my momma used to tell me these crazy things

/ She used to tell me my daddy was an evil man, She used to tell me he hated

me” on “Kill You”. However, his references to the same subject on this song are

delivered without any gravitas, simply as words to fill the bar: “I’m like Chef

Boyardee in this bitch / Send a bomb to my mom’s lawyer / I’m a problem for ya

boy…” Notice how the reference to his mom is completely isolated in theme or

even sense from what comes before or after.It’s just filler.

Or how about his earlier habit of

rapping directly to kids, to corrupt and influence them? “Hey kids? Do you like

violence? / Do you want to see my stick 9 inch nails through each one of my

eyelids?” (from his pre-2004 song, “My Name Is”) “Who woulda thought? / That

Slim Shady would be something that you woulda bought / That woulda made you get

a gun and shoot at a cop / I just said it – I ain’t know if you’d do it or

not.” (again pre-2004, “Who Knew?”) But examine the same theme or subject

matter in “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em”: “Like yo fada fuckin’ yo mada” (Bar 17.) Again,

the lines are delivered without any wit, cleverness, or subtlety.

Furthermore, at

times he just completely ignores all habits of English language syntax – “Them no up to par” (bar 30), not “they

aren’t up to par” in, “Mi-ster fly-by-the-seat-of-his-pants pantsed out, fall, [NOT FELL] hit the tram-po-line,

bounced, and grabbed a pair of stilts.” (Bar 14 and 15.) Again, this is still

allowing for the normal amount of leeway we give rappers in the crafting of

their raps. Furthermore, he just gets words wrong: “fucking fictitional characters”. “Fictitional”

is not a word; he was clearly going for fictional, but needed the extra

syllable to fit the bar. This cutting of corners is very uncharacteristic of

Em, and shows that he isn’t quite completely on point here.

In sum, this is

the isolation of the musical variable we had discussed before – Eminem isn’t

make any textual, semantic sense.

But can the same

be said of his musical sense?

As

awful as Eminem’s crafting of textual continuity is here, his rap as a strictly

musical phenomenon is that much more awesome. His flow absolutely kills it. The

word “flow” is a general musical term covering all of the musical aspects of a

rapper’s rap. It is comprised mainly of the manipulation of accent. In my view,

there are 3 types of accent in rap: poetic accent, verbal accent, and metric

accent. The way these accents interact goes a long way to describing how a

rapper’s flow behaves musically.

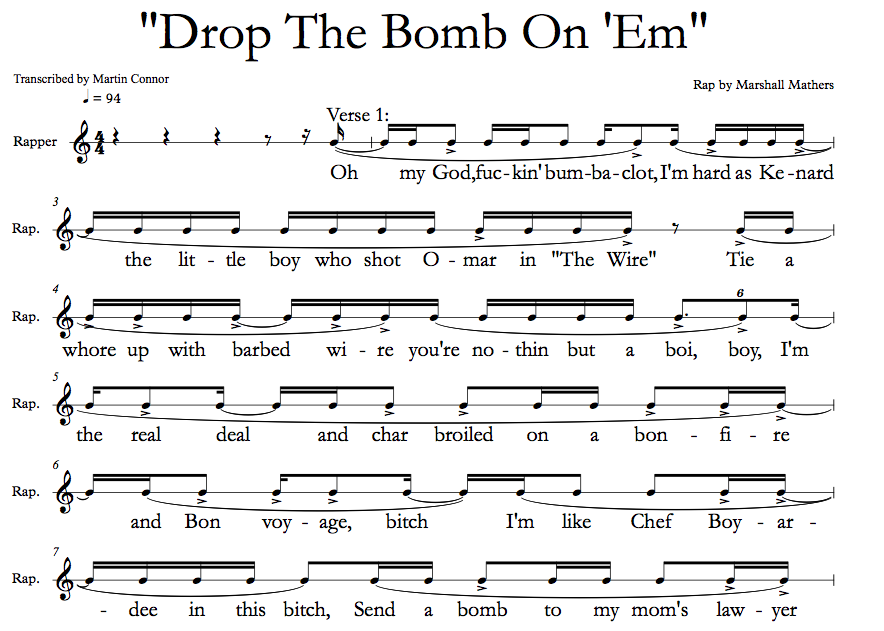

“Poetic accent” is a natural emphasis

that occurs in the listeners ear on word-notes that are acted upon poetically:

for instance, they are rhymed together, or alliterated together. Such an

example can be seen early on in “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em”, in bar 2, when Eminem

says, “I’m HARD as keNARD” –notice how these words stand out naturally in your

ear.The poetic accent is here denoted by the little mathematical greater-than

sign under rhymed words:

Verbal accent is the natural emphasis

that a certain syllable in a word receives. For instance, in the word “verbal”,

the correct English speaker will place the accent on the first syllable. We will see verbal accent in action a little later on in this post.

Rappers use verbal accent to determine where to place words in the metric bar.

Speaking of which…

Metric accent is the natural emphasis

that a bar (also called a measure) of music receives. This is determined by the

music’s time signature, which is that little fraction-looking thing at the

start of a piece of music. It is important tto note, however, that it is NOT a

fraction. The top and bottom numbers separately indicate two different things.

The bottom number determines what note value receives the beat: if it is a “4”,

the quarter note receives the beat, if “2”, the half-note, if “8”, the 8th

note, and more. The top number says how many of the beat are in each bar. So if

it’s “4”, there are 4 beats, if “6”, 6 beats, and so on. About 95% of all rap music

is in 4/4. That means that there are 4 quarter notes per bar. Such is the case

with “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em.” In a bar of 4/4, the natural accents of the bar

are such that beats 1 and 3, are called the “strong” beats, while beats 2 and 4

are the weak beats. This has been notated below:

So,

to the title of this article: how are you supposed to listen to rap?

Interesting, by completely ignoring the rap: try not to pay attention to what the rapper is saying. Instead, listen

only for the manipulation of the above accents. Tune out the specific words

until you just hear a steady noise of the human voice. I’ve specifically picked

this song to illustrate my point here, because Eminem doesn’t make any sense at

all (as we’ve already established), so it does you no good anyway to listen to

what he’s saying. Yes, it’s important that he says, “I’m hard as kenard,” but

only because of the rhyme, not because of the point he’s trying to make. To

help you do this, I’ve rendered the song roughly in MIDI.

I

suggest – nay, command – you to bob your head up and down to the music while

listening to it. Your nods should correspond to the eighth notes of the 4/4

bar, so your head should be at its lowest or highest point in the nod every

time the piano plays its chord. Eminem’s rap is played by the wooden block

sound. I’ve underlined and emphasized the word-notes that receive a poetic

accent, such as all of the rhymed words, by doubling the wood block sound at

those points. I’ve only notated the 3 verses. Everytime there is an extended

period of lack of sound from the wooden block, it means the next verse is about

to start. Verse 1 in the MIDI starts at 0:02, verse 2 at 0:48, and verse 3 at

1:54. In the real song, Verse 1 starts at 0:19, verse 2 at 1:23, and verse 3 at

2:47. Hear the midi sound below. Just go to the website below and press the big orange play button:

While you’re listening, remember,

BOB YOUR HEAD, and feel all of the accents. Feel it in bar 2, where Eminem

leaves the music hanging mid-sentence by rapping, “I’m hard as Kenard…”,

completing his grammatical idea in the next bar by adding “the little boy who

shot Omar in ‘The Wire’”. (Notice how Eminem here adds a new dimension to the

textual meaning of this song by actually going and BLOWING A HUGE SPOILER ABOUT

THE MOST INTERESTING PLOTLINE OF THE GREATEST TV SHOW EVER. Seriously, if he

had just kept spitting nonsensical things it would’ve been one thing, but to go

and say who kills Omar? Man.) The little curved line under the musical notes,

from the word “I’m” in bar 2 to the word “Wire” in bar 3 indicates a

grammatical phrase. These are complete grammatical ideas, such as a sentence,

that we hear all together in our ears as one single unit. The description of

where a rapper places the start and end of their grammatical phrases in

relationship to the beginning of the bar line goes a long way towards

describing a rapper’s flow. Eminem, thus, here propels the music forward by

leaving the sentence hanging at the bar line and completing the idea in the

next bar. Keep bobbing your head so you feel it not just mentally but also

kinesthetically. Eminem continues to leave grammatical phrases hanging and then

completing them later on throughout this whole song.

Next,

feel how the poetic accents keep falling in different places throughout the

beginning of verse 1, in the first 6 bars notated. That is, they never always

fall on beat 3, or always on beat 4, or in any regular pattern. For instance,

in bar 4, the word “boy” falls off the beat during beat 4; in the next bar, bar

5, it is rhymed with “broiled”, but that falls right on beat 3, not on the

“and” of the 4th beat, like “boy” does in beat 4. A similar thing is

done when “barbed” is rhymed with “char”: they don’t fall in the same place in

the bar. This is a technically complex technique to pull off. Furthermore,

there is an average of about 4 poetic accents during the first verse. This is a

very high average of accents to pull off. Comparatively, in the so-called

Golden Age of rap, rappers like Tupac would put their rhymes (poetic accents)

only at the end of the bar. That would mean 1 poetic accent per bar, because he

rhymed largely in a couplet, ABAB form. Eminem, meanwhile, quadruples that

rate. Additionally, Eminem utilizes internal rhyming. This means that he places

poetic accents inside the grammatical phrases that we identified earlier. This

also stands in stark contrast to rap during its early days.

In

more dazzling verbal trickery, Eminem, in bar 8, fits 6 poetic accents in a

row: “I’m a problem for ya boy” are all syllables that are rhymed with the

vowel sounds of “bomb to my mom’s lawyer.” (It is important to note here that

it is not always how the word is spelled in the transcription that is the way

Eminem pronounces the word, which is the only important pronunciation when

determining whether words are rhymed together or not.”) So keep bobbing your

head, and keep feeling how those poetic accents are emphases that keep showing

up in different places in the bar. However, Eminem does also place rhymes in

the same metrical place from one bar to the next at certain points. For

instance, in the pairs of bars 8 and 9 and bars 10 and 11, respectively, the

rhymes fall in the same place – at the end of the bar. “Tom Sawyer” and “stomp

on ya” both fall on beat 4, and “fairy tales” and “ferris wheels” both fall on

beat 4 as well. It seems so far that there is very little Eminem can’t

manipulate when he is writing his raps.

In

verse 2, Eminem ups the ante. He actually drops some pretty good lines this

verse, text-wise: “Boy I’m the real McCoy, you little boys can’t evne fill

voids / Party’s over kids, kill the noise, here come the kill joys” is sick,

along with “Yeah you’re fresh than most, I’m just doper than all”, but as

mentioned before, they are more than evened out by “Get some R&R and

marinate in some marinara.” That line itself could be considered a microcosm of

the whole song: the wordplay is sick, with its heavy amount of accents, but it

just doesn’t make any sense. Of especial note should be bars 31 to 40. The

rhymes on beat 3 in all of these bars are just sick: they are “blow up the

spot”, “boy I’m a star”, “boy, I’m DeSean”, “Boy, you’re a fraud”, “blow you to

sod”, “boy you’re the plot”, “avoid it or not”, definitely “Detroit is a rock”,

and, finally, “what point it will stop.” Listen especially to this part to how

every beat 3, with all of its poetic accents, stands out.

Let’s

talk more about grammatical phrases. In verse 3, Eminem changes a lot where

grammatical phrases start and end. For instance, sometimes they fall completely

in the bar, such as at bar 44: “I’m Michael Spinks with the belt.” Other times,

they are fall completely within the bar, bar 46: “I’m sick as hell, boy, you

better run and tell someone else.” The word-notes “I’m sick as” and “Bring in”

in the next bar are just considered pick-up notes to the bars that follow them;

they just lead to the next bar, and aren’t really part of the bar itself. Sometimes

his grammatical phrases are short, such as the ones we just looked at. At other

times, they are very long, such as the phrase that starts “And to that boy…”

and ends “black and red little sweater” in bars 47 to 48. Furthermore, in that

phrase, he displaces the verbal accent of his words from lining up with the

metrical accent of bar that we saw before, with the strong and weak beats. For

instance, in the word “Excedrin”, the middle syllable, “-ce-“, gets the accent,

but musically, the syllable “drin” falls right on beat 2. Thus, Eminem has

divorced the verbal accent from the metrical accent of the bar. He does the

same thing with the word “sweater” in bar 49. This phenomenon actually reveals

a lot about how the beat and rap in general work. One reason why rappers can

rhyme such complex rhythms in their raps is that the beat remains largely

constant. It doesn’t change throughout the song; the bass kicks are on beats 1

and 3, and the snare hits are on beats 2 and 4. This shows that without the

constant strong-weak, strong-weak beat, the rap would fall into chaos because

the listener couldn’t follow the accents of the rap that are constantly

changing, which wouldn’t be balanced by the constant feel of the unchanging

beat. But again, this just shows that Eminem can do it all.

So,

if we were to describe Eminem’s flow in general, it would be as follows: Eminem

is capable of a great number of different styles of flow. He can internally

rhyme, end rhyme, and fill up bars with multiple accents. He utilizes both musical

phrases and through-composed styles of writing. Furthermore, he is adept at

manipulating where in the bar the grammatical phrases fall. In short, he can do

it all. In a very general sense, however, Eminem’s flow is denoted by 4 or so

poetic accents per bar, with rhymes coming in groups of 2 or more, and lots of

internal rhyming as well as tons of syncopation.

The

complimentary song to “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em” would be another Dre beat, “How We

Do”, featuring Game and 50 Cent from Game’s 2004 album, “The Documentary.”

Here, the entire musical tension is based around whether the poetic accent

lines up with the metrical accent or not. Throughout the first half of Game’s

first verse, the poetic accent is always off the beat and syncopated.

Throughout the second half, it is always on the beat. Then, in Game’s 2ndverse, after having set up your expectations, he then manipulates them, as all

great music-makers do – whether composers, producers, rappers, songwriters,

whoever. Because in his second verse, he switches constantly between the poetic

accent being on the beat, then off the beat, then on the beat, on the beat

again maybe, then off, then on, then off, then off, and so on. And, as more

evidence, listen to what words Dre doubletracks in the production (answer

provided at end of post.) What do they all have in common? Interesting, huh?

You can find a much more in-depth analysis of this song and a greater

explanation of what I just said in my Rap Analysis #1, found here.

Hopefully

this helps some of you enjoy the genre as much as I do. And if you’re looking

for other rappers who are as skilled as Em, my short list is Mos Def, Talib

Kweli, and Jean Grae. Check out my other posts, such as #7 – Jean Grae and #12

– Mos Def, to see what it is they do. Feel free to follow me on twitter

@ComposersCorner, and to email me about lessons on rapping and producing! The

complete transcription is provided below. Oh, and Dre doubles all of the vocals

from Game that are rhymes – that is, poetic accents.

Very interesting way to listen to hip-hop/rap

ReplyDeleteClearly that's what I call a marvelous article! Do you use this website for your personal purposes only or you actually exploit it to get profit with its help?

ReplyDeleteNo, no profit yet. Working on writing a book though! Thanks for the kind words!

DeleteRead the whole thing, awesome work. Gives a very impression about the rap music than one would assume.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting read and to me shows the genius of Eminem. He can literally create a great song that technically says nothing.

ReplyDeleteAlso...The word "bomboclat" actually has meaning. Bomboclat:

A Jamaican expression meant to convey shock or surprise

"I won $50,000 in the lotto!"

"BOMBOCLAT!"

Also it is a diss: Bomboclat is also a garbled form of Battlecat. Battlecat (Kevin Gilliam, more on wikipedia) is one of Snoop Dogg’s favorite producers.

He is behind Snoop Dogg’s diss song against Eminem called "Secrets (feat. Kokane)" from the album Malice n Wonderland (2009). In the song, Snoop Dogg comments on Eminem‘s big ears, something that hounts Eminem since his early childhood. Now the icing on the cake is that a band called „Elephant man“ has a song called „Bomboclat“ (watch on youtube).

Another diss song where Snoop Doggs refers to Eminem’s big ears is “Turtleneck And Chain” by The Lonely Island (feat. Snoop Dogg), where Snoop Dogg says, "Rabbit kicked Dogg“. It's all part of a diss. And I wonder how many of his rhymes we don't actually comprehend. I haven't studied all of this song but I'm getting a feeling there is more to it than we understand. I'm hard as Kenard, the little boy who shot Omar in The Wire.

A beautiful subliminal reference to Snoop Dogg. Eminem goes hard on this song, right the first two lines are dedicated to identify his target.

The Wire is a TV crime drama. Kenard is a young member of Michael’s crew. Michael killed Snoop in the last episode of the series. That’s right, Snoop... a fictional character called Felicia "Snoop" Pearson (read more on wiki). My info is taken from this website and is not my own. Maybe you can analyze it more: http://www.snoopeminembeef.com/2012/06/eminem-drop-bomb-on-em-diss-song.html?m=1

Also as a side note. I really enjoy reading your information. I naturally know how to listen to rap music. When I first hear a new song I don't even listen to what is said but how the rappers sounds go with the beat to create that Head bobbing associated with all of rap music

ReplyDeleteAlso reading further into that website. Some of the verses you didn't understand actually have meaning. The song isn't just non sense. I didn't understand them either till I read this:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.snoopeminembeef.com/2012/06/eminem-drop-bomb-on-em-diss-song.html?m=1