The greatest Dr. Dre song of all time, the song on which he achieved perfection, is...

"The Next Episode"

Now, this might be a rather unsurprising winner of our Top 10 list. But let's go over why it's so amazing.

First, consider the form. It's an open-ended, through-composed form, meaning there are no sections that repeat such as a verse or chorus. Each rapper, Dre, then Snoop, then Nate, just rap/sing their verse. It thus is not very repetitive, and stands up to multiple replays.

Second, this song, single as it was, would serve as a great introduction for listeners and critics alike to the new soundworld that Dre was going to be opening up to them. It has everything: the dark, natural minor piano chords, played on a piano that you'd never find in an audio sound world, with the equally sombre, macabre, foreboding bass strings. No dominant buzz synths to be found around here, like "The Chronic" or "Doggystyle" to a lesser extent. The emphasis on melodic instruments rather than the beat (snare, bass, etc.) are all to be identified here.

Finally, though, what makes this song my favorite is its historical context. You have to consider where Dre was at this point in his career: he had already achieved huge fame with NWA, the one band who, more than any other, would go on to give birth to the coming era of gangsta rap through g-funk and other categories. He followed that up with a successful solo album, "The Chronic", and by launching the solo career of someone whose career is still ongoing and entering his 3rd decade of work, Snoop Dogg (or Snoop Lion, as I hear he's called now.)

People were wondering, how could he ever top what he's done so far? How could he live up to expectations? And instead of giving them what they wanted, Dre gave listeners what he wanted. And so you end up with the Holy Trinity of West Coast rap - Dre, Snoop Dogg, and Nate Dogg - putting together a sick song. If ever there were proof that rappers need to roll squad deep in order to be truly bad-ass, it's this song. It's the history that each rapper brings to this song that makes it so remarkable. The story each tells is what gives the song narrative depth.

Think of it like this: an author writes a story, a novel, perhaps, about characters. In rap, though, rappers don't just become those characters in a story they create, they are those characters. They create their own character's story, their character's attributes, likes, dislikes, and so on, and then live out their character's lives on their songs. It's telling that almost universally all rappers choose different names when they rap - Marshall Mathers becomes Eminem/Slim Shady, Calvin Broadus becomes Snoop Dogg, Curtis Jackson becomes 50 Cent, and so on. Even if the lives of the actual person himself and his rap persona line up at times, such as when Eminem/Marshall discusses his daughter Kim, do we really to believe that these people have killed as many people as they say they have? Of course not. But it's this suspension of disbelief that makes rap have such levels to it. We don't have the orienting effect of seeing a character's story played out on a movie screen that constantly reminds us we're watching a movie, or the physical pages in a book that remind us that we're reading something written by someone who is not in the story. There is nothing to check the rapper's facts against, certainly because we don't know them as people, so we accept what we hear as real, unconsciously or consciously.

And this is the story that I most enjoy about Dre. At this point in time, he is The Godfather of rap. He has given birth to the next generation of music, a musical scene that will dominate for 20 years (gangsta rap.) His prodigy, Snoop Dogg, multi-platinum album seller, backs him up on this. And then Nate Dogg jumps on and explains what it's really all about.

I'll be doing a summary of the Top 10 list, such as why certain things fell where, along with honorable mentions, in another post coming up soon.

Hope you enjoyed it!

Sign Up For Email

Friday, September 21, 2012

Saturday, September 15, 2012

Top Ten Dre Songs Of All Time - #2

The 2nd greatest Dr. Dre song of all time is...

"About Me", with Raekwon and Busta Rhymes

Click the above link to hear it.

Now, this sick is just straight fire. Very similar to number 4 on this list, called "Get You Some", and in fact they were released around the same time.

First off, who would've expected that Dre, West Coast, G-Funk, LA, would ever hook up with Raekwon, Wu-Tang Clan gambino, Staten Island? The fact that two of the greatest got together for this song is just awesome. Rae absolutely kills it in his own unique styles - the slang he drops, in case you don't know, is just crazy ill. I'm sorry, but that's the only way to describe it. Although not from this song, his lines:

"Serial numbers is braille, so when you rub against it feels all twos" is sick. If you can't figure out what that means, then head on over to rapgenius.com and look up the song. When it clicks for you you'll be amazed.

Meanwhile, he continues to drop lines like, "Wash a nigga's face with the mac / smoke 'em like steak-ums." Excuse me, but wash a nigga's face with the mac? He's not sayin' he's gonna shoot you...he's not sayin' he's gonna make you backflip...he's sayin' he's gonna wash your face with the mac. Damn. I mean, we know what it mean from the context, but really, how much more sinister and generally bad-ass does it sound to say "wash"?

Furthermore, we should take note from Rae's career of how to age gracefully as a rapper. He didn't try to keep talkin' about the same shit, but instead set up a whole album's story loosely based around an aging drug dealer in the city.

But the beat is sick as well. If you listen to the piano again, it's the quintessential Dre piano: block chords, HUGE sound, playing natural minor harmonies. This is where Dre's piano ideas, which were first incepted way back with the start of G-funk, around The Chronic album, would become the most elaborate. The long scale that he plays in the right hand piano, being 4 bars long and all scalar motion, is quite an idea. Then, there's the snare, which just like #4, bangs in your ears. You're almost being assaulted by Dre's music at this point.

Come back for #1 tomorrow. If you look back over the list, and realize what song hasn't been on yet, it's pretty easy to figure out what's number one. This song, "About Me", definitely challenged for the spot, but there's no way, what with the context that the #1 song was created in, that it wasn't gonna take the top spot.

And again,

@ComposersCorner

!

"About Me", with Raekwon and Busta Rhymes

Click the above link to hear it.

Now, this sick is just straight fire. Very similar to number 4 on this list, called "Get You Some", and in fact they were released around the same time.

First off, who would've expected that Dre, West Coast, G-Funk, LA, would ever hook up with Raekwon, Wu-Tang Clan gambino, Staten Island? The fact that two of the greatest got together for this song is just awesome. Rae absolutely kills it in his own unique styles - the slang he drops, in case you don't know, is just crazy ill. I'm sorry, but that's the only way to describe it. Although not from this song, his lines:

"Serial numbers is braille, so when you rub against it feels all twos" is sick. If you can't figure out what that means, then head on over to rapgenius.com and look up the song. When it clicks for you you'll be amazed.

Meanwhile, he continues to drop lines like, "Wash a nigga's face with the mac / smoke 'em like steak-ums." Excuse me, but wash a nigga's face with the mac? He's not sayin' he's gonna shoot you...he's not sayin' he's gonna make you backflip...he's sayin' he's gonna wash your face with the mac. Damn. I mean, we know what it mean from the context, but really, how much more sinister and generally bad-ass does it sound to say "wash"?

Furthermore, we should take note from Rae's career of how to age gracefully as a rapper. He didn't try to keep talkin' about the same shit, but instead set up a whole album's story loosely based around an aging drug dealer in the city.

But the beat is sick as well. If you listen to the piano again, it's the quintessential Dre piano: block chords, HUGE sound, playing natural minor harmonies. This is where Dre's piano ideas, which were first incepted way back with the start of G-funk, around The Chronic album, would become the most elaborate. The long scale that he plays in the right hand piano, being 4 bars long and all scalar motion, is quite an idea. Then, there's the snare, which just like #4, bangs in your ears. You're almost being assaulted by Dre's music at this point.

Come back for #1 tomorrow. If you look back over the list, and realize what song hasn't been on yet, it's pretty easy to figure out what's number one. This song, "About Me", definitely challenged for the spot, but there's no way, what with the context that the #1 song was created in, that it wasn't gonna take the top spot.

And again,

@ComposersCorner

!

Friday, September 14, 2012

Top Ten Dre Songs Of All Time #3

This one isn't much of a surprise - maybe only that it's not at the top. It bears repeating that any of the songs on this list would likely top a "Best Of" list of any other artist's discography - but not Dre's. The 3rd song is:

Eminem's Real Slim Shady

Most people already know why this song is amazing, so I'll try not to belabor the point. First, there is what I've elsewhere called the greatest orchestration decision of all time, by the choice of a harpsichord to play the keyboard part. The irony of an obscene rap song being accompanied by a Renaissance/Baroque era instrument should not be lost on the listener. Eminem, besides keeping the flow tight, also delivers one of the funniest songs in rap as well. No wonder parents were up in arms over Eminem's lyrics back in the day.

So up until now, the roster of artists we have on the top 10 list is:

1. Dre himself

2. Busta

3. Game

4. Nas

5. Q-Tip

6. Jay-Z (ghost verse)

7. Obie Trice

8. 50 Cent

9. Eminem

We're coming up another missing one in the next song...definitely a must hear as well, as well as an unexpected one.

Eminem's Real Slim Shady

Most people already know why this song is amazing, so I'll try not to belabor the point. First, there is what I've elsewhere called the greatest orchestration decision of all time, by the choice of a harpsichord to play the keyboard part. The irony of an obscene rap song being accompanied by a Renaissance/Baroque era instrument should not be lost on the listener. Eminem, besides keeping the flow tight, also delivers one of the funniest songs in rap as well. No wonder parents were up in arms over Eminem's lyrics back in the day.

So up until now, the roster of artists we have on the top 10 list is:

1. Dre himself

2. Busta

3. Game

4. Nas

5. Q-Tip

6. Jay-Z (ghost verse)

7. Obie Trice

8. 50 Cent

9. Eminem

We're coming up another missing one in the next song...definitely a must hear as well, as well as an unexpected one.

Thursday, September 13, 2012

Top Ten Dre Songs Of All Time - #4

The 4th greatest song of all time with Dr. Dre on the beat is...

"Get You Some", off Busta Rhymes' "Big Bang Album."

Click Here To Listen

Now, this song was a serious challenger for the best Dre beat of all time, and we'll get to why soon. But Busta kinda lets us down on the verse, all the opening to the 2nd verse is amazing...but his rhymes aren't tight. It should be noted that this song is the very one that I strive to emulate and the heights to which I strive to attain when I make my own beats.

Let me walk you through this beat though.

So the girl starts singing with that Arabian inflection or whatever, and you're like WTF am I about to hear?

And then the drums and beat kick in, and you're still like what the fuckkkkk.

Cuz what instrument is that? Is that - no, it can't be. Is that a mofo'in chinese gu-gin on the beat? It's gotta be a plucked lute instrument of some kind - maybe even a pipa. And that snare - is it literally a gunshot? Yes, Dre has used a gunshot as a snare before, and even used the sound of shovel digging, but the way this snare assaults your ear drum is just something else. It's like it resonates in the very dome of your skull or something.

Then, is Q-Tip really on the chorus? Did 2 of all the time greats really hook-up on this beat?

And Busta starts rapping in his declamatory style, like he's a goddamn twisted minister or something at his pulpit, and you've realized that Dre has just taken you to a place you really might not have wanted to go. This beat just sounds dangerous. Like it might actually hurt you.

And then the HUGE piano sound comes in - I mean seriously, is that even a piano? Have you ever heard a piano in real life that actually sounds like that? And the harmonies are so dirty, it's just nasty. Gross. Filthy.

And the start of the 2nd verse - Busta skips the first verse and you're like, "I just got shitted on." Yes. Yes you did.

So Dre just fucked up the rest of your day. Now go home and just try to do something about it.

"Get You Some", off Busta Rhymes' "Big Bang Album."

Click Here To Listen

Now, this song was a serious challenger for the best Dre beat of all time, and we'll get to why soon. But Busta kinda lets us down on the verse, all the opening to the 2nd verse is amazing...but his rhymes aren't tight. It should be noted that this song is the very one that I strive to emulate and the heights to which I strive to attain when I make my own beats.

Let me walk you through this beat though.

So the girl starts singing with that Arabian inflection or whatever, and you're like WTF am I about to hear?

And then the drums and beat kick in, and you're still like what the fuckkkkk.

Cuz what instrument is that? Is that - no, it can't be. Is that a mofo'in chinese gu-gin on the beat? It's gotta be a plucked lute instrument of some kind - maybe even a pipa. And that snare - is it literally a gunshot? Yes, Dre has used a gunshot as a snare before, and even used the sound of shovel digging, but the way this snare assaults your ear drum is just something else. It's like it resonates in the very dome of your skull or something.

Then, is Q-Tip really on the chorus? Did 2 of all the time greats really hook-up on this beat?

And Busta starts rapping in his declamatory style, like he's a goddamn twisted minister or something at his pulpit, and you've realized that Dre has just taken you to a place you really might not have wanted to go. This beat just sounds dangerous. Like it might actually hurt you.

And then the HUGE piano sound comes in - I mean seriously, is that even a piano? Have you ever heard a piano in real life that actually sounds like that? And the harmonies are so dirty, it's just nasty. Gross. Filthy.

And the start of the 2nd verse - Busta skips the first verse and you're like, "I just got shitted on." Yes. Yes you did.

So Dre just fucked up the rest of your day. Now go home and just try to do something about it.

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

Top Ten Dre Songs Of All Time #5 - In Da Club

The 5th greatest song of all time in Dr. Dre's song is...

"In Da Club"

Click here to hear it

This comes from 50 Cent's debut album on Eminem's Shady album, called "Get Rich Or Die Tryin'", released in 2003. Now, this song is amazing, not just for it's production choices, but also the mixing process. Mixing, from wikipedia, is defined as:

"In audio recording, audio mixing is the process by which multiple recorded sounds are combined into one or more channels, most commonly 2-channel stereo. In the process, the source signals' level, frequency content, dynamics, and panoramic position are manipulated and effects such as reverb may be added. This practical, aesthetic, or otherwise creative treatment is done in order to produce a mix that is more appealing to listeners."

So it's not just that Dre chose brass to play the main riff of the song - it's how effing huge those horns sound. The rhythm, syncopated as it is, is just so driving. If you've ever been out, perhaps "in da club", and this song comes on, then you know why this song deserves to be #5. It holds up to multiple replays. 50 also spits a pretty good verse for this being pretty clear a club track - that doesn't always work out, just hear 50's song "Fire" from some time later.

#4 coming out tomorrow...a criminally underheard Dre song, come back fuh sho

"In Da Club"

Click here to hear it

This comes from 50 Cent's debut album on Eminem's Shady album, called "Get Rich Or Die Tryin'", released in 2003. Now, this song is amazing, not just for it's production choices, but also the mixing process. Mixing, from wikipedia, is defined as:

"In audio recording, audio mixing is the process by which multiple recorded sounds are combined into one or more channels, most commonly 2-channel stereo. In the process, the source signals' level, frequency content, dynamics, and panoramic position are manipulated and effects such as reverb may be added. This practical, aesthetic, or otherwise creative treatment is done in order to produce a mix that is more appealing to listeners."

So it's not just that Dre chose brass to play the main riff of the song - it's how effing huge those horns sound. The rhythm, syncopated as it is, is just so driving. If you've ever been out, perhaps "in da club", and this song comes on, then you know why this song deserves to be #5. It holds up to multiple replays. 50 also spits a pretty good verse for this being pretty clear a club track - that doesn't always work out, just hear 50's song "Fire" from some time later.

#4 coming out tomorrow...a criminally underheard Dre song, come back fuh sho

Monday, September 10, 2012

Top Ten Dre Songs, #6 - Forgot About Dre

The #6 greatest song of all time in Dr. Dre's oeuvre is...

Forgot About Dre - click here

This is another song that you might expect to hear higher up in the list. Now, don't get me wrong, this song is amazing - the strings sound so foreboding, and Eminem delivers an extended verse (more than 16 bars long) that is certainly one of the most memorable in his output, if not one of his greatest verses ever. Notice how he raps through the small distorted guitar solo - it just makes him sound so fierce, rapping for so long. Dre is also sick, but by this point, unlike "The Chronic" album and his work with NWA, he didn't write his rap. He had someone write his rap for him, which is known as ghostwriting. This is something everyone should know about Dre - he doesn't write his own raps. I think that's okay though, since he still delivers the rap with good delivery and hitting all his rhythms, and he's an amazing producer. Besides, when Eminem can interpret how Dre feels so well, like he does on Ice Cube's "Hello", why would Dre need to write his own beats?

But again, this song suffers from the production not being deep enough - I don't think it stands up to a ridiculous amount of replays, which is what I give it. There aren't any of the elaborating ideas that we find in his output after "1999", like in the song "Oh!", which you can find in another rap analysis of mine, #6.

Also, "Forgot About Dre" is a pretty good indicator of Dre's artistic direction post "1999." He would take the orchestral strings one step further, and turn to using real orchestral instruments whiled still preserving the minor third sound world. Also, note how Dre uses strings in his own work in contrast to other producers. Rather than using strings as soft, dramatic, kind of melodramatic elements, he uses them as strong, foreboding elements. Definitely a hallmark of his style.

Come back tomorrow for #5! It'll be a song that pretty much everyone knows...

Forgot About Dre - click here

This is another song that you might expect to hear higher up in the list. Now, don't get me wrong, this song is amazing - the strings sound so foreboding, and Eminem delivers an extended verse (more than 16 bars long) that is certainly one of the most memorable in his output, if not one of his greatest verses ever. Notice how he raps through the small distorted guitar solo - it just makes him sound so fierce, rapping for so long. Dre is also sick, but by this point, unlike "The Chronic" album and his work with NWA, he didn't write his rap. He had someone write his rap for him, which is known as ghostwriting. This is something everyone should know about Dre - he doesn't write his own raps. I think that's okay though, since he still delivers the rap with good delivery and hitting all his rhythms, and he's an amazing producer. Besides, when Eminem can interpret how Dre feels so well, like he does on Ice Cube's "Hello", why would Dre need to write his own beats?

But again, this song suffers from the production not being deep enough - I don't think it stands up to a ridiculous amount of replays, which is what I give it. There aren't any of the elaborating ideas that we find in his output after "1999", like in the song "Oh!", which you can find in another rap analysis of mine, #6.

Also, "Forgot About Dre" is a pretty good indicator of Dre's artistic direction post "1999." He would take the orchestral strings one step further, and turn to using real orchestral instruments whiled still preserving the minor third sound world. Also, note how Dre uses strings in his own work in contrast to other producers. Rather than using strings as soft, dramatic, kind of melodramatic elements, he uses them as strong, foreboding elements. Definitely a hallmark of his style.

Come back tomorrow for #5! It'll be a song that pretty much everyone knows...

Saturday, September 8, 2012

Top Ten Dre Songs Of All Time, #7 - Oh!

The number 7 all time greatest Dr. Dre song is...

"Oh!", off Obie trice's 2004 album "Cheers", featuring Busta Rhymes.

Listen to it here

For why the beat is amazing, I'll just refer you to my analysis of the complete song, found here, where I completely break the beat down.

As for the rap...

Obie Trice puts it down. His flow the first verse is especially amazing. Take note of how long he keeps the rhyme on the vowel sound "oh" going (notice how that is also the title of the song, and the major musical idea of Busta's chorus: "Oh - oh I had you yellin out when I bag the 30/30 rifle"... clever, ain't it?"

Just take note:

"O, that's the road you on, oh no

I'm down for the rightful tone of fo' fo'

Don't ever try to send a nigga home, no no

I know you wanna catch me at Sunoco

Show me that you're loco, put holes in my photo

NOPE!, HOPE!, hold toast, no jokes, send slugs through your Polo

Just cause our thug roll solo

Impose on grown folk, be a cold negro."

Damn.

This song also speaks volumes about the rap empire Dre has established with all of the talent he directly and indirectly found. First, he gave birth to the whole genre of gangsta rap with NWA. Then, he established Snoop Dogg with "The Chronic" and "Doggystyle." Then, after working with 2 of the greatest emcees of all time in Nas and AZ with the group "The Firm", he went on to start Aftermath Records, which would sign Eminem. Eminem would go on to find Shady Records, which signed 50 Cent and Obie Trice, featured here. 50 Cent would start G-Unit, which found Game, as well as Lloyd Banks and Young Buck. Busta would be on aftermath at one point too.

Dre is the godfather of an imposing rap mafia family. Not bad.

"Oh!", off Obie trice's 2004 album "Cheers", featuring Busta Rhymes.

Listen to it here

For why the beat is amazing, I'll just refer you to my analysis of the complete song, found here, where I completely break the beat down.

As for the rap...

Obie Trice puts it down. His flow the first verse is especially amazing. Take note of how long he keeps the rhyme on the vowel sound "oh" going (notice how that is also the title of the song, and the major musical idea of Busta's chorus: "Oh - oh I had you yellin out when I bag the 30/30 rifle"... clever, ain't it?"

Just take note:

"O, that's the road you on, oh no

I'm down for the rightful tone of fo' fo'

Don't ever try to send a nigga home, no no

I know you wanna catch me at Sunoco

Show me that you're loco, put holes in my photo

NOPE!, HOPE!, hold toast, no jokes, send slugs through your Polo

Just cause our thug roll solo

Impose on grown folk, be a cold negro."

Damn.

This song also speaks volumes about the rap empire Dre has established with all of the talent he directly and indirectly found. First, he gave birth to the whole genre of gangsta rap with NWA. Then, he established Snoop Dogg with "The Chronic" and "Doggystyle." Then, after working with 2 of the greatest emcees of all time in Nas and AZ with the group "The Firm", he went on to start Aftermath Records, which would sign Eminem. Eminem would go on to find Shady Records, which signed 50 Cent and Obie Trice, featured here. 50 Cent would start G-Unit, which found Game, as well as Lloyd Banks and Young Buck. Busta would be on aftermath at one point too.

Dre is the godfather of an imposing rap mafia family. Not bad.

Friday, September 7, 2012

Rap Analysis #0 - How To Listen Musically To Rap

This might be the most important rap analysis point of all. It explains the points of departure for all of the rest of my analyses. For that reason, I've numbered it "0", as it is the starting place. You might even want to go through this a couple times until you really get it, and then head to analysis #1, on Game's "How We Do", to see everything I explain here in action.

-->

-->

As I hear more and more of the

negative criticisms of rap, new ideas are starting to occur to me. One of the

most interesting is that, perhaps, people who don’t like rap music simply don’t

know how to listen to it. This might

be a strange idea to some, to have to learn how to listen to something. Yes,

most of us can hear things – but how do we really listen to something, by which

I mean the music in its proper context, a context that reveals just as much

about the music as the music itself does. I would posit that this idea is not

as farfetched as it might first seem. Yes, when we read a book, there is the

story on the page in front of us that we enjoy. But if we are aware of the

greater narrative of the book, such as themes and symbols, inevitably our

enjoyment of the experience deepens. Such a metaphor can be applied to music.

This

whole phenomenon has struck me in a certain scientific sense. (What follows is

a gross oversimplification, and might even be an outright misrepresentation of

the scientific method – but such is the result when you have a humanities

student trying to explain it.) I think of it in terms of a scientific

experiment, where we need to isolate variables and observe their response. We

have some variables that we want to measure, and we can only do so accurately

if we are able to isolate them. Roughly, what I have suggested in the previous

paragraph is that there is a musical meaning to rap that is able to be divorced

from its textual meaning while still having an internally consistent meaning

(note, however, that the two can never be studied completely in isolation from

each other, as we shall see.) But how could we ever possibly isolate these,

respectively, musical and textual variables? Certainly, there is no rap (here

referring to both the musical and textual – that is, the lyrics – elements of

rap) that has a textual meaning but no music, and there is no rap that has a

musical meaning but makes no textual sense…or is there?

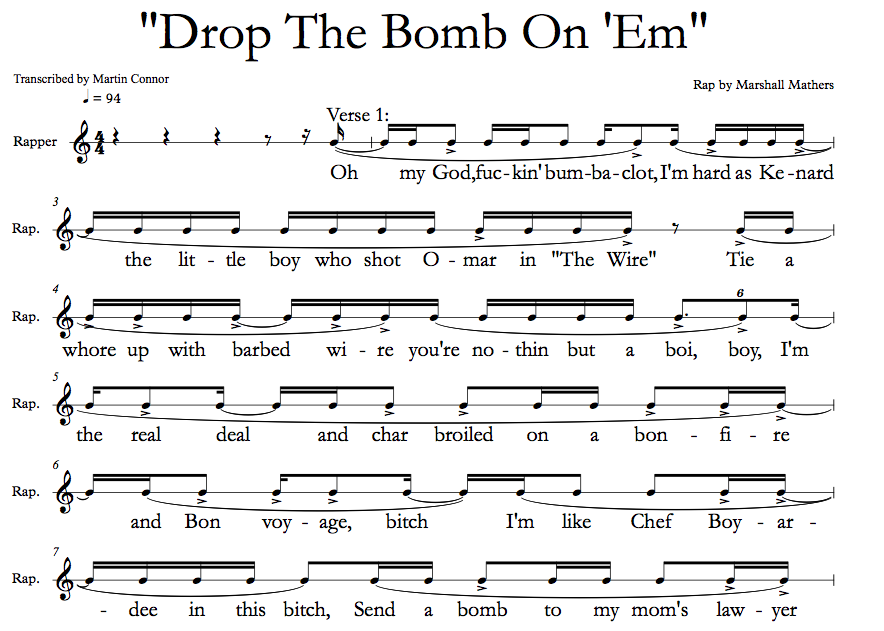

Enter

what I currently consider THE most interesting (not necessarily in a positive

sense) rap song of all time, Eminem’s “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em”, produced by Dr.

Dre, from the album “Relapse”, released in 2009. This was Eminem’s first album

in 5 years, since his 2004 “Encore”, a hiatus due to his writer’s block and an

addiction to prescription sleeping medication. This song is located at an

exceptional instance of an artist who is in the unique stance of knowing that

his place in the pantheon of all-time-rap greats has already been secured, and

he is still in his prime writing years (He was about 36 at the time). He is

making a comeback – people haven’t heard from him in 5 years. How is he

supposed to follow up “Encore”? “The Marshall Mathers LP”? “The Slim Shady LP”?

“The Eminem Show”? The man has won Grammys, popular and critical acclaim,

worked with the greatest producers of all time, and yet he still has to prove

himself because of his hiatus. He hasn’t forgotten how to rap – in stark

contrast to other legends in similar but certainly not the same circumstance,

like Jay-Z or Lil Wayne, he hasn’t fallen off. But he’s just had about 50% of

his lyrical material considered “off-limits” to him: he is now trying to go

clean, so that means no rapping about weed, shrooms, vicodin, oxycodin, all of

that stuff (Just check out his song “Drug Ballad” – but maybe the title lets

you know all you need to know.) So he can still rap – but what the hell is he

supposed to write about? This is the central tension, certainly palpable and

almost tangible, in this song.

The

answer is, figuratively, “nothing.” Eminem manages to rap over 55 bars without

actually saying anything. What’s more is, this goes beyond the normal amount of

nonsense that the listener naturally allows when listening to rap, simply

because, as I believe, it’s predominantly a musical phenomenon, not a textual

(or even poetic, in the general sense) phenomenon. Let’s take a popular example

today:

In Bobby Ray’s “Ray Bans”, he raps

“My whole team getting green, and I ain’t talking about pottery.” Now, not all

pottery is green. I think when he says pottery he really is referring to

plants, most of which are green. Still, the connection is thin. But Eminem goes

beyond this point.

Nothing he says in

this song really has any real connection to anything outside of his world.

Let’s just say you don’t come away from the song pondering in what sense,

exactly, Eminem is “like Chef Boyardee in this bitch.” Or what metaphoric

meaning he is reaching for when he describes himself as “Captain America on

ferris wheels.” And don’t overthink it. Okay, yes, rap is a genre built on

reference and allusion – but these tools lose their power when no one at all

gets them, even if they are references at all (which they aren’t, here.) This

kind of shit is all over the song. What the fuck is “bumbaclot?” When Eminem

tells me that I think I’m Tom Sawyer, does he really think I’m a 19th

century juvenile dilenquent living along the Mississippi? When he tells me I

should “Get some R&R and marinate in some marinara,” what really should I

do? And these are simply the most egregious of the violations of not just

commonsense, but sense.

The

saddest part of this, though, is when Eminem reaches for lifesavers in the form

of themes and ideas he used to rap about all the time. For instance, even if

you haven’t heard Eminem’s music, you know that his relationship with his mom

has been less than perfect. His earlier references to this subject come across

as tortured and agonized when examined, such as his raps “99% of my life I was

lied to / I just found out my mom does more dope than I do” in “My Name Is”, or

‘When I was just a little baby boy, my momma used to tell me these crazy things

/ She used to tell me my daddy was an evil man, She used to tell me he hated

me” on “Kill You”. However, his references to the same subject on this song are

delivered without any gravitas, simply as words to fill the bar: “I’m like Chef

Boyardee in this bitch / Send a bomb to my mom’s lawyer / I’m a problem for ya

boy…” Notice how the reference to his mom is completely isolated in theme or

even sense from what comes before or after.It’s just filler.

Or how about his earlier habit of

rapping directly to kids, to corrupt and influence them? “Hey kids? Do you like

violence? / Do you want to see my stick 9 inch nails through each one of my

eyelids?” (from his pre-2004 song, “My Name Is”) “Who woulda thought? / That

Slim Shady would be something that you woulda bought / That woulda made you get

a gun and shoot at a cop / I just said it – I ain’t know if you’d do it or

not.” (again pre-2004, “Who Knew?”) But examine the same theme or subject

matter in “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em”: “Like yo fada fuckin’ yo mada” (Bar 17.) Again,

the lines are delivered without any wit, cleverness, or subtlety.

Furthermore, at

times he just completely ignores all habits of English language syntax – “Them no up to par” (bar 30), not “they

aren’t up to par” in, “Mi-ster fly-by-the-seat-of-his-pants pantsed out, fall, [NOT FELL] hit the tram-po-line,

bounced, and grabbed a pair of stilts.” (Bar 14 and 15.) Again, this is still

allowing for the normal amount of leeway we give rappers in the crafting of

their raps. Furthermore, he just gets words wrong: “fucking fictitional characters”. “Fictitional”

is not a word; he was clearly going for fictional, but needed the extra

syllable to fit the bar. This cutting of corners is very uncharacteristic of

Em, and shows that he isn’t quite completely on point here.

In sum, this is

the isolation of the musical variable we had discussed before – Eminem isn’t

make any textual, semantic sense.

But can the same

be said of his musical sense?

As

awful as Eminem’s crafting of textual continuity is here, his rap as a strictly

musical phenomenon is that much more awesome. His flow absolutely kills it. The

word “flow” is a general musical term covering all of the musical aspects of a

rapper’s rap. It is comprised mainly of the manipulation of accent. In my view,

there are 3 types of accent in rap: poetic accent, verbal accent, and metric

accent. The way these accents interact goes a long way to describing how a

rapper’s flow behaves musically.

“Poetic accent” is a natural emphasis

that occurs in the listeners ear on word-notes that are acted upon poetically:

for instance, they are rhymed together, or alliterated together. Such an

example can be seen early on in “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em”, in bar 2, when Eminem

says, “I’m HARD as keNARD” –notice how these words stand out naturally in your

ear.The poetic accent is here denoted by the little mathematical greater-than

sign under rhymed words:

Verbal accent is the natural emphasis

that a certain syllable in a word receives. For instance, in the word “verbal”,

the correct English speaker will place the accent on the first syllable. We will see verbal accent in action a little later on in this post.

Rappers use verbal accent to determine where to place words in the metric bar.

Speaking of which…

Metric accent is the natural emphasis

that a bar (also called a measure) of music receives. This is determined by the

music’s time signature, which is that little fraction-looking thing at the

start of a piece of music. It is important tto note, however, that it is NOT a

fraction. The top and bottom numbers separately indicate two different things.

The bottom number determines what note value receives the beat: if it is a “4”,

the quarter note receives the beat, if “2”, the half-note, if “8”, the 8th

note, and more. The top number says how many of the beat are in each bar. So if

it’s “4”, there are 4 beats, if “6”, 6 beats, and so on. About 95% of all rap music

is in 4/4. That means that there are 4 quarter notes per bar. Such is the case

with “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em.” In a bar of 4/4, the natural accents of the bar

are such that beats 1 and 3, are called the “strong” beats, while beats 2 and 4

are the weak beats. This has been notated below:

So,

to the title of this article: how are you supposed to listen to rap?

Interesting, by completely ignoring the rap: try not to pay attention to what the rapper is saying. Instead, listen

only for the manipulation of the above accents. Tune out the specific words

until you just hear a steady noise of the human voice. I’ve specifically picked

this song to illustrate my point here, because Eminem doesn’t make any sense at

all (as we’ve already established), so it does you no good anyway to listen to

what he’s saying. Yes, it’s important that he says, “I’m hard as kenard,” but

only because of the rhyme, not because of the point he’s trying to make. To

help you do this, I’ve rendered the song roughly in MIDI.

I

suggest – nay, command – you to bob your head up and down to the music while

listening to it. Your nods should correspond to the eighth notes of the 4/4

bar, so your head should be at its lowest or highest point in the nod every

time the piano plays its chord. Eminem’s rap is played by the wooden block

sound. I’ve underlined and emphasized the word-notes that receive a poetic

accent, such as all of the rhymed words, by doubling the wood block sound at

those points. I’ve only notated the 3 verses. Everytime there is an extended

period of lack of sound from the wooden block, it means the next verse is about

to start. Verse 1 in the MIDI starts at 0:02, verse 2 at 0:48, and verse 3 at

1:54. In the real song, Verse 1 starts at 0:19, verse 2 at 1:23, and verse 3 at

2:47. Hear the midi sound below. Just go to the website below and press the big orange play button:

While you’re listening, remember,

BOB YOUR HEAD, and feel all of the accents. Feel it in bar 2, where Eminem

leaves the music hanging mid-sentence by rapping, “I’m hard as Kenard…”,

completing his grammatical idea in the next bar by adding “the little boy who

shot Omar in ‘The Wire’”. (Notice how Eminem here adds a new dimension to the

textual meaning of this song by actually going and BLOWING A HUGE SPOILER ABOUT

THE MOST INTERESTING PLOTLINE OF THE GREATEST TV SHOW EVER. Seriously, if he

had just kept spitting nonsensical things it would’ve been one thing, but to go

and say who kills Omar? Man.) The little curved line under the musical notes,

from the word “I’m” in bar 2 to the word “Wire” in bar 3 indicates a

grammatical phrase. These are complete grammatical ideas, such as a sentence,

that we hear all together in our ears as one single unit. The description of

where a rapper places the start and end of their grammatical phrases in

relationship to the beginning of the bar line goes a long way towards

describing a rapper’s flow. Eminem, thus, here propels the music forward by

leaving the sentence hanging at the bar line and completing the idea in the

next bar. Keep bobbing your head so you feel it not just mentally but also

kinesthetically. Eminem continues to leave grammatical phrases hanging and then

completing them later on throughout this whole song.

Next,

feel how the poetic accents keep falling in different places throughout the

beginning of verse 1, in the first 6 bars notated. That is, they never always

fall on beat 3, or always on beat 4, or in any regular pattern. For instance,

in bar 4, the word “boy” falls off the beat during beat 4; in the next bar, bar

5, it is rhymed with “broiled”, but that falls right on beat 3, not on the

“and” of the 4th beat, like “boy” does in beat 4. A similar thing is

done when “barbed” is rhymed with “char”: they don’t fall in the same place in

the bar. This is a technically complex technique to pull off. Furthermore,

there is an average of about 4 poetic accents during the first verse. This is a

very high average of accents to pull off. Comparatively, in the so-called

Golden Age of rap, rappers like Tupac would put their rhymes (poetic accents)

only at the end of the bar. That would mean 1 poetic accent per bar, because he

rhymed largely in a couplet, ABAB form. Eminem, meanwhile, quadruples that

rate. Additionally, Eminem utilizes internal rhyming. This means that he places

poetic accents inside the grammatical phrases that we identified earlier. This

also stands in stark contrast to rap during its early days.

In

more dazzling verbal trickery, Eminem, in bar 8, fits 6 poetic accents in a

row: “I’m a problem for ya boy” are all syllables that are rhymed with the

vowel sounds of “bomb to my mom’s lawyer.” (It is important to note here that

it is not always how the word is spelled in the transcription that is the way

Eminem pronounces the word, which is the only important pronunciation when

determining whether words are rhymed together or not.”) So keep bobbing your

head, and keep feeling how those poetic accents are emphases that keep showing

up in different places in the bar. However, Eminem does also place rhymes in

the same metrical place from one bar to the next at certain points. For

instance, in the pairs of bars 8 and 9 and bars 10 and 11, respectively, the

rhymes fall in the same place – at the end of the bar. “Tom Sawyer” and “stomp

on ya” both fall on beat 4, and “fairy tales” and “ferris wheels” both fall on

beat 4 as well. It seems so far that there is very little Eminem can’t

manipulate when he is writing his raps.

In

verse 2, Eminem ups the ante. He actually drops some pretty good lines this

verse, text-wise: “Boy I’m the real McCoy, you little boys can’t evne fill

voids / Party’s over kids, kill the noise, here come the kill joys” is sick,

along with “Yeah you’re fresh than most, I’m just doper than all”, but as

mentioned before, they are more than evened out by “Get some R&R and

marinate in some marinara.” That line itself could be considered a microcosm of

the whole song: the wordplay is sick, with its heavy amount of accents, but it

just doesn’t make any sense. Of especial note should be bars 31 to 40. The

rhymes on beat 3 in all of these bars are just sick: they are “blow up the

spot”, “boy I’m a star”, “boy, I’m DeSean”, “Boy, you’re a fraud”, “blow you to

sod”, “boy you’re the plot”, “avoid it or not”, definitely “Detroit is a rock”,

and, finally, “what point it will stop.” Listen especially to this part to how

every beat 3, with all of its poetic accents, stands out.

Let’s

talk more about grammatical phrases. In verse 3, Eminem changes a lot where

grammatical phrases start and end. For instance, sometimes they fall completely

in the bar, such as at bar 44: “I’m Michael Spinks with the belt.” Other times,

they are fall completely within the bar, bar 46: “I’m sick as hell, boy, you

better run and tell someone else.” The word-notes “I’m sick as” and “Bring in”

in the next bar are just considered pick-up notes to the bars that follow them;

they just lead to the next bar, and aren’t really part of the bar itself. Sometimes

his grammatical phrases are short, such as the ones we just looked at. At other

times, they are very long, such as the phrase that starts “And to that boy…”

and ends “black and red little sweater” in bars 47 to 48. Furthermore, in that

phrase, he displaces the verbal accent of his words from lining up with the

metrical accent of bar that we saw before, with the strong and weak beats. For

instance, in the word “Excedrin”, the middle syllable, “-ce-“, gets the accent,

but musically, the syllable “drin” falls right on beat 2. Thus, Eminem has

divorced the verbal accent from the metrical accent of the bar. He does the

same thing with the word “sweater” in bar 49. This phenomenon actually reveals

a lot about how the beat and rap in general work. One reason why rappers can

rhyme such complex rhythms in their raps is that the beat remains largely

constant. It doesn’t change throughout the song; the bass kicks are on beats 1

and 3, and the snare hits are on beats 2 and 4. This shows that without the

constant strong-weak, strong-weak beat, the rap would fall into chaos because

the listener couldn’t follow the accents of the rap that are constantly

changing, which wouldn’t be balanced by the constant feel of the unchanging

beat. But again, this just shows that Eminem can do it all.

So,

if we were to describe Eminem’s flow in general, it would be as follows: Eminem

is capable of a great number of different styles of flow. He can internally

rhyme, end rhyme, and fill up bars with multiple accents. He utilizes both musical

phrases and through-composed styles of writing. Furthermore, he is adept at

manipulating where in the bar the grammatical phrases fall. In short, he can do

it all. In a very general sense, however, Eminem’s flow is denoted by 4 or so

poetic accents per bar, with rhymes coming in groups of 2 or more, and lots of

internal rhyming as well as tons of syncopation.

The

complimentary song to “Drop The Bomb On ‘Em” would be another Dre beat, “How We

Do”, featuring Game and 50 Cent from Game’s 2004 album, “The Documentary.”

Here, the entire musical tension is based around whether the poetic accent

lines up with the metrical accent or not. Throughout the first half of Game’s

first verse, the poetic accent is always off the beat and syncopated.

Throughout the second half, it is always on the beat. Then, in Game’s 2ndverse, after having set up your expectations, he then manipulates them, as all

great music-makers do – whether composers, producers, rappers, songwriters,

whoever. Because in his second verse, he switches constantly between the poetic

accent being on the beat, then off the beat, then on the beat, on the beat

again maybe, then off, then on, then off, then off, and so on. And, as more

evidence, listen to what words Dre doubletracks in the production (answer

provided at end of post.) What do they all have in common? Interesting, huh?

You can find a much more in-depth analysis of this song and a greater

explanation of what I just said in my Rap Analysis #1, found here.

Hopefully

this helps some of you enjoy the genre as much as I do. And if you’re looking

for other rappers who are as skilled as Em, my short list is Mos Def, Talib

Kweli, and Jean Grae. Check out my other posts, such as #7 – Jean Grae and #12

– Mos Def, to see what it is they do. Feel free to follow me on twitter

@ComposersCorner, and to email me about lessons on rapping and producing! The

complete transcription is provided below. Oh, and Dre doubles all of the vocals

from Game that are rhymes – that is, poetic accents.

Labels:

Rap Music Analysis

Top Ten Dre Songs, #8 - Game, "How We Do"

The #8 song of my Top 10 Countdown of The Greatest Dr. Dre Songs of All Time comes from "the 2nd dopest nigga from compton you'll ever hear / the first one only puts out albums every 7 years" (amazing quote.) Yes, it's Game feat. fellow former G-Unit member, 50 Cent, from Game's debut album from 2004, "The Documentary", with the song "How We Do", heard on youtube here.

If you haven't heard that album, I strongly suggest checking it out. The number of props that Game hands out on that album to NWA and the West Coast scene in general is off the charts, especially on the "The Documentary" song from the album.

This song is quintessential Dre, featuring all of his hallmarks: foreboding strings, toned down (in a very specific sense) drums, just sick production all around. If you know me at all, you know that this song stays in heavy rotation on my ipod. If not, well you, you know now.

This song beats out "Don't Get Carried Away" and more surprisingly "Still D.R.E." because Game and 50 both lay it down in each of their 2 respective verses. Furthermore, the production is a little deeper, and remains intriguing and interesting even after multiple listens. There are more musical ideas in the beat that come and go a little more frequently, giving it a musical depth that "Still D.R.E." doesn't have, while I believe that song might have a better central beat. "Don't Get Carried Away", meanwhile, while having an amazing verse from Nas, is bookended by 2 so-so verses from Busta.

Enjoy! If you liked this post and the song, check out the more in-depth analysis I did of it here, where I discuss how to listen to rap music (Say whaaa?)

Come back tomorrow for #7!

If you haven't heard that album, I strongly suggest checking it out. The number of props that Game hands out on that album to NWA and the West Coast scene in general is off the charts, especially on the "The Documentary" song from the album.

This song is quintessential Dre, featuring all of his hallmarks: foreboding strings, toned down (in a very specific sense) drums, just sick production all around. If you know me at all, you know that this song stays in heavy rotation on my ipod. If not, well you, you know now.

This song beats out "Don't Get Carried Away" and more surprisingly "Still D.R.E." because Game and 50 both lay it down in each of their 2 respective verses. Furthermore, the production is a little deeper, and remains intriguing and interesting even after multiple listens. There are more musical ideas in the beat that come and go a little more frequently, giving it a musical depth that "Still D.R.E." doesn't have, while I believe that song might have a better central beat. "Don't Get Carried Away", meanwhile, while having an amazing verse from Nas, is bookended by 2 so-so verses from Busta.

Enjoy! If you liked this post and the song, check out the more in-depth analysis I did of it here, where I discuss how to listen to rap music (Say whaaa?)

Come back tomorrow for #7!

Thursday, September 6, 2012

Top Ten Dre Songs of All Time - #9 - "Don't Get Carried Away"

The 9th best Dr. Dre song of all time, as determined by yours truly, is...

"Don't Get Carried Away"

Honestly, where to start with this song?

There are 3 verses: 2 Busta Rhymes verses bookend the middle verse by Nas. The song is a single from Busta Rhymes' 2006 album when he was on Dre's Aftermath Records, called "The Big Bang" (which will show up again later on in this countdown.) Busta holds it down; not his worse, but definitely not his best. Nas, however, delivers what, in my estimation, is one of the greatest rap verses of all time. The execution of all elements of flow is flawless: tight rhymes, interesting rhythms, a flow that, appropriately, flows - that is, the line of tension is constantly being manipulated - with the added impressiveness of what I've identified as cross-rhythms in the music. I go much more in-depth on the vesre in my #3 Analysis, which you can navigate to by clicking the preceding link. This is about Dre's production, anyway, not Nas' verse, so let's move on!

As can also be seen in my survey of Dre's orchestration decisions between 2000 and 2009, the production choices in this song are simply sick. Dre's instruments include a carillon bell, a hard-hitting church organ, staccato strings (cellos? double basses?) playing the bass line, legato strings playing riffs, timpani drums playing bass lines, legato brass during the verses, as well as his characteristic elaborative ideas, long pedals, and sectionally dividing musical ideas (see the post link above for longer and better explanations.) I can't think of many other songs that even use those instruments, and certainly no other songs besides Dre's that use them in that combination. What is very instrumenting in Dre's production in general beginning with 1999's "2001" and continuing up until today is his general concentration of all parts of the production besides the drums. His drums (snare, bass, hi-hat, other percussion elements) usually do not stand out very much in the song; it is not that they do not impart a heavy effect to the feeling of the song, which of course they do (as anyone who has heard his "In Da Club" knows), but it is just that they have a lot of their identifying frequencies removed. That is, the bass kick only really sounds like a thud, usually; and the snare drum is usually a real, acoustic one, rather than a crafted synth sound. All of these things are identifiable to a certain extent in this song; the clap snare drum is a little out of the ordinary for Dre's production at this time.

Furthermore, the organ during the chorus of this song is sick. As identified in the first post in the series, found here, Dre's sound from "2001" forwards is very much defined by a natural minor scale. The organ in this chorus expands on that. The chords sound very crunchy and dissonant, due to some dissonant intervals, like seconds. Also, as noted before Nas and Busta are on this song. They are just 2 of the ultimately 12 artists who will appear in total on this list. It is very satisfying about Dre's career that he seems to have done at least one G.O.A.T. (Greatest Of All Time) song with one of these artists. Who will show up tomorrow? Sorry man, gotta come back tomorrow to find out.

"Don't Get Carried Away"

Honestly, where to start with this song?

There are 3 verses: 2 Busta Rhymes verses bookend the middle verse by Nas. The song is a single from Busta Rhymes' 2006 album when he was on Dre's Aftermath Records, called "The Big Bang" (which will show up again later on in this countdown.) Busta holds it down; not his worse, but definitely not his best. Nas, however, delivers what, in my estimation, is one of the greatest rap verses of all time. The execution of all elements of flow is flawless: tight rhymes, interesting rhythms, a flow that, appropriately, flows - that is, the line of tension is constantly being manipulated - with the added impressiveness of what I've identified as cross-rhythms in the music. I go much more in-depth on the vesre in my #3 Analysis, which you can navigate to by clicking the preceding link. This is about Dre's production, anyway, not Nas' verse, so let's move on!

As can also be seen in my survey of Dre's orchestration decisions between 2000 and 2009, the production choices in this song are simply sick. Dre's instruments include a carillon bell, a hard-hitting church organ, staccato strings (cellos? double basses?) playing the bass line, legato strings playing riffs, timpani drums playing bass lines, legato brass during the verses, as well as his characteristic elaborative ideas, long pedals, and sectionally dividing musical ideas (see the post link above for longer and better explanations.) I can't think of many other songs that even use those instruments, and certainly no other songs besides Dre's that use them in that combination. What is very instrumenting in Dre's production in general beginning with 1999's "2001" and continuing up until today is his general concentration of all parts of the production besides the drums. His drums (snare, bass, hi-hat, other percussion elements) usually do not stand out very much in the song; it is not that they do not impart a heavy effect to the feeling of the song, which of course they do (as anyone who has heard his "In Da Club" knows), but it is just that they have a lot of their identifying frequencies removed. That is, the bass kick only really sounds like a thud, usually; and the snare drum is usually a real, acoustic one, rather than a crafted synth sound. All of these things are identifiable to a certain extent in this song; the clap snare drum is a little out of the ordinary for Dre's production at this time.

Furthermore, the organ during the chorus of this song is sick. As identified in the first post in the series, found here, Dre's sound from "2001" forwards is very much defined by a natural minor scale. The organ in this chorus expands on that. The chords sound very crunchy and dissonant, due to some dissonant intervals, like seconds. Also, as noted before Nas and Busta are on this song. They are just 2 of the ultimately 12 artists who will appear in total on this list. It is very satisfying about Dre's career that he seems to have done at least one G.O.A.T. (Greatest Of All Time) song with one of these artists. Who will show up tomorrow? Sorry man, gotta come back tomorrow to find out.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

Top Ten Dre Songs Of All Time - #10

Welcome to the beginning of my countdown of the top 10 Dre songs of all time. Many people will be surprised by what's on here, what's not, and especially where certain legendary song ("Forgot About Dre", "Still D.R.E.", end up.) By I promise that this list has been formed in my mind over a period of multiple years and through deep familiarity and knowledge of Dre's entire Discography, from his Wreckin Cru of the 80s, to NWA, down through "The Chronic" and Snoop's "Doggystyle", and then the come up on Aftermath/Shady/G-Unit records and his godfathering of the careers of Eminem, 50 Cent, and Game.

In making this list, I've had to be a little coldhearted. I've had to listen to all of Dr. Dre's songs in the current context of today's musical world. Which songs are still most relevant today? Which of them still feel new to us today? Which can we listen to over, and over, and over, without them ever getting out? This means that, at times, I've had to disregard the influence certain songs had at the time they came out in order to rather pick the songs that they led to (hint, hint.)

In choosing these songs, I've also picked the song based on everything: production, beats, rap, the whole deal. So if a rapper kills it on a certain song, based on my perception that Dre probably had something to do with how their rap was crafted and delivered, I took that into account.

But without any more delay, the first song of the Top Ten Dre Songs of All Time:

Drum roll.......

"Still D.R.E."

(click above to hear the song)

Probably a shocker for many of you out there. Yes, the beat is absolutely dirt. It's sick. It's nasty. But the rap isn't quite there. I think it was ghostwritten by the D.O.C., who, while being a very good rapper in his own right, simply couldn't measure up to Eminem's work on the rest of the 1999 album "Chronic 2001." We'll see the effects of Em's lyricism with the placement of certain songs up and down this list.

Furthermore, the beat, compared to Dre's later works, comes across as a bit one-dimensional. There is no elaboration or variation of different structural sections through hallmark musical ideas, like we saw in my examination of Dre's orchestration decisions between 2000 and 2009, Rap Post Analysis #10, which you can navigate to on the right.

Now, however, for what's good about the beat. As is usual with Dre, each part of the beat plays its own very specific part as being a part of the whole, which is where all the parts come together to be more than the sum of their parts. He fills out the whole frequency range of his instruments, with a high clean guitar block chord part, with the foreboding, ominous low strings. It perfectly conjures up the West Coast life that Dre strove to depict, and was certainly an unprecedented soundworld to evoke in rap up until that time. Even today, the beat sounds fresh. Dre's natural minor world (the keys are in a minor key without any 6th or 7th scale degree inflections) would go on to form a cornerstone for songs over the rest of his career, including everything from 50's "In Da Club" to Busta Rhymes "Get You Some." We'll be exploring this soundworld more in depth as we move through the list.

So yes, the beat is sick. But it suffers a little from a less than stellar rap, and Dre not yet knowing what he would learn over the rest of his career.

Look tomorrow for the 9th Top Ten Dre Song Of All Time!

In making this list, I've had to be a little coldhearted. I've had to listen to all of Dr. Dre's songs in the current context of today's musical world. Which songs are still most relevant today? Which of them still feel new to us today? Which can we listen to over, and over, and over, without them ever getting out? This means that, at times, I've had to disregard the influence certain songs had at the time they came out in order to rather pick the songs that they led to (hint, hint.)

In choosing these songs, I've also picked the song based on everything: production, beats, rap, the whole deal. So if a rapper kills it on a certain song, based on my perception that Dre probably had something to do with how their rap was crafted and delivered, I took that into account.

But without any more delay, the first song of the Top Ten Dre Songs of All Time:

Drum roll.......

"Still D.R.E."

(click above to hear the song)

Probably a shocker for many of you out there. Yes, the beat is absolutely dirt. It's sick. It's nasty. But the rap isn't quite there. I think it was ghostwritten by the D.O.C., who, while being a very good rapper in his own right, simply couldn't measure up to Eminem's work on the rest of the 1999 album "Chronic 2001." We'll see the effects of Em's lyricism with the placement of certain songs up and down this list.

Furthermore, the beat, compared to Dre's later works, comes across as a bit one-dimensional. There is no elaboration or variation of different structural sections through hallmark musical ideas, like we saw in my examination of Dre's orchestration decisions between 2000 and 2009, Rap Post Analysis #10, which you can navigate to on the right.

Now, however, for what's good about the beat. As is usual with Dre, each part of the beat plays its own very specific part as being a part of the whole, which is where all the parts come together to be more than the sum of their parts. He fills out the whole frequency range of his instruments, with a high clean guitar block chord part, with the foreboding, ominous low strings. It perfectly conjures up the West Coast life that Dre strove to depict, and was certainly an unprecedented soundworld to evoke in rap up until that time. Even today, the beat sounds fresh. Dre's natural minor world (the keys are in a minor key without any 6th or 7th scale degree inflections) would go on to form a cornerstone for songs over the rest of his career, including everything from 50's "In Da Club" to Busta Rhymes "Get You Some." We'll be exploring this soundworld more in depth as we move through the list.

So yes, the beat is sick. But it suffers a little from a less than stellar rap, and Dre not yet knowing what he would learn over the rest of his career.

Look tomorrow for the 9th Top Ten Dre Song Of All Time!

Tuesday, September 4, 2012

Rap Analysis Glossary of Terms

Hey there! Most likely you've been referred here from another one of my posts, telling you to go here in order to ground yourself in the basics. The most important thing to know when reading my analyses is the importance of accent in rap - verbal, metrical, and poetic. Go through this glossary in order so you feel like you have a good grip on things - as might be expected, though, you will get much fuller explanations of these concepts in the full posts. See my #3 Rap Analysis on Nas for accent, and my #8 analysis of Common's "I Used To Love H.E.R." for a discussion of grammatical phrasing. for musical phrases, see #2, on Eminem's "Business." For rhymes, see Mos Def, #11. For a good discussion of flow, see #12, Big Sean.

Enjoy!

Glossary:

Verbal accent – The natural way in which words are pronounced. For

instance, in the word “verbal”, the accent is on the syllable “ver-“, so that

it is pronounced (and notated in my transcriptions) as “VER-bal.”

Verbal Accent Displacement – The act of displacing a word’s natural

verbal stress from the metric accent of a bar as determined by the time

signature. For instance, Nas in “Don’t Get Carried Away” – QUOTE

Verbal Accent Adjustment – the changing in the pronunciation of a

word to match up with the metric accent of a bar’s time signature.

Poetic accent – An accent that is created when a rapper links two

different notes by rhyming them together, alliterating them, or through other

poetic means.

Metric accent – The accent imparted to a musical measure by virtue

of its time signature; for instance, in 4/4, beats 1 and 3 are the strong

beats, and beats 2 and 4 are the weak beats. Thus, we say that beats 1 and 3

receive the metric accent.

Flow – An all-inclusive term for referring to the strictly musical

qualities of a rapper’s work. Flow is affect by articulation, rate of poetic

accents, the nature and use of syntactical and/or musical phrases, and so on.

Rap – A musical vocal idiom of the inflected speaking voice characterized by constant

rhythms and a focus on tight manipulation of accent and articulation.Whenever

the term “rap” is used in this work, it should be taken to refer to both the

musical and textual qualities of a rapper’s work, as opposed to the other parts

of the typical rap song, i.e., the beat (bass kick, snare, etc.), the

accompaniment (piano chords in the background), and so on.

Rap Music - Refers to the genre of rap in general.

Production – Refers to those parts of a typical rap song that is

everything besides the rapper’s work, such as the bass kick, snare, and any

other percussive elements, as well as melodic and accompanimental ideas found

in any specified-pitch instruments (such as pianos, violins, etc.) Note: the

word “beat” should never be used to refer to these musical elements, to avoid

confusion with the idea of a “beat” found in a time signature.

Beat – The rhythmic duration that receives stress, as determined by

a time signature. For instance, in 6/8, the bottom number, the 8, designates

which rhythmic duration receives the beat: here, the eighth note.

Musical Phrase – Strictly in this work’s context, a short musical

idea whose rhythmic structure is repeated at least once. NOTE: This is vastly

different from the definition of a musical phrase in other musical contexts,

such as classical music.

Grammatical Phrase – The natural phrasing imparted to a rapper’s

work by organizers of syntax, such as commas, conjunctions (like the words

“and”, “or”, “but”, etc.), periods, and so on. Indicated notationally by a

curved line under the notes from one note to another one.

Tyranny of 4 – Refers to the over-emphasis of the number 4 or its

derivatives in the organization of almost all rap music. For instance, there

are 4 beats to a bar, different structural elements of a song (verses,

choruses, etc.) are usually organized in multiples of 4 (ending at 8, 12, 16,

etc., number of bars.) The variation of this natural tendency for the

organization of music is a major way forward towards creating new, innovative

rap music.

Metrical Transferrence – The changing of the metric placement of a musical phrase by a rapper; for instance, in Biggie “Hypnotize”, the changing of a music phrase from starting on the beat to starting off the beat.

Metrical Transferrence – The changing of the metric placement of a musical phrase by a rapper; for instance, in Biggie “Hypnotize”, the changing of a music phrase from starting on the beat to starting off the beat.

Internal Rhyming – The technique of placing rhymes inside

syntactical phrases; typical of rappers like Mos Def, Nas, and Eminem.

End rhyming – The technique of placing rhymes at the end of

syntactical phrases; typical of most rappers like Kanye West.

Block rhyming – The repetition of a set order of vowels in a rhyme

scheme over and over, without changing their order.

Syllabic rhyming – Rhyme schemes that are based on a single or more

vowel sound, like Eminem in “Lose Yourself:” Their order can change

if more than one vowel sound is involved.

Multisyllabic Rhymes – Rhymes made on more than one syllable.

Isosyllabic rhymes - Rhymes

made on a single syllable.

Rapper – The person who generates both the words and rhythms of a

rap.

Rate of Poetic Accent – How many accents there are per measure in a

certain rap.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)