Below is the interview I just conducted with Talib Kweli. I asked him a lot of the same questions that I asked Jean Grae

here and Pharoahe Monch

here. It’ll be helpful to aspiring rappers, big hip hop fans, and new fans too. I ask him how he writes his rhymes, what advice he can give to starting rappers, and more. Enjoy!

Composer’s Corner: You grew up in a household with some professors in it. For instance, your mom is an English professor at Medgar Evers College, and your dad was an administrator at Adelphi University. What is your formal education history of music like? Have you ever taken piano lessons or anything like that?

Talib Kweli: I think I played a recorder in junior high school. At one point for like a month I took guitar lessons from a kid in my high school. I didn’t really learn shit though. Then there was a movie a couple years ago that never got made but that I got a part for. I played a drummer. I took about 4 months of drum lessons to make it look it real.

Composer’s Corner: It sounds like none of these impacted the rapper and musician you are today because those experiences were scattershot.

Talib Kweli: Those things were just things I tried. I can’t say I learned a whole lot. If anything what I know musically from rapping I probably brought to those things more than the other way around.

Composer’s Corner: Did you have anyone in particular who helped you learn the basics of rap, saying, “This is how you count beats, this is how you count bars,” stuff like that?

Talib Kweli: I approach music from a very intellectual standpoint. I’m not saying that to brag. I’m just saying I don’t feel like I’m necessarily as naturally talented at it as some of my favorite musicians. I think that’s what the interesting about Black Star always was, with Mos Def. I can write really well. But Mos Def is more organic. Even in the way we recorded. When we were recording with Black Star, I’d have to take the beat and listen to it for a while, for a couple weeks, before I was like, “Okay, I’m ready.” And then write it down on the paper. Mos would just hear it and start saying things.

Composer’s Corner: What is your compositional process? You were getting into it a little bit. You always have the beat first and you listen to it for a while before you know what you want to do?

Talib Kweli: That was back then, and I’ve evolved and changed and tried different things over the years. When I first started listening to Hip Hop, I didn’t really listen in an investing way to Hip Hop until like 1987, 1988. Groqwing up in New York you hear it. I knew Run-D.M.C. and Beastie Boys, but I didn’t really listen to Hip Hop. When I got to junior high school is when I started listening to Hip Hop, because that’s what all the kids were listening to. As soon as I started listening to it I started writing my own rhymes and I’d give them to kids in my neighborhood who were already rappers. I was already writing plays and poetry. I was definitely a gifted writer when I was young, so the writing was there. But it was the musicality of it that I had to come to learn. So when I first started rapping, when I gained the confidence to rap under my own name, what I would do is I’d have composition notebooks full of rhymes. Just full of rhymes. And when I started meeting producers as a teenager, and going into studios for the first time, I would try to say these rhymes to established beats. And I think that’s where my style developed from. To say rhymes that were already written with a syncopation in my head or written with a rhythm in my head and try to fit them to different beats. And over the years I’ve really gotten out of that habit and I’ve developed a habit where I want to hear the beat and the rhymes come directly out of the beat. As soon as I hear a beat, rhyme s start popping into my head, and I’m like, “Okay, I like that beat.”

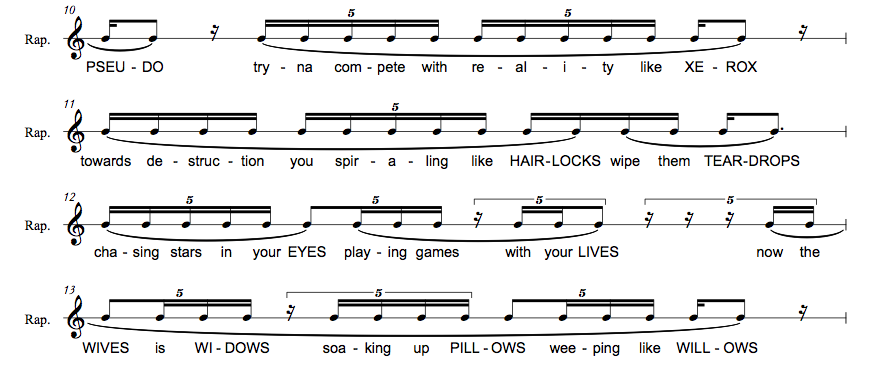

Composer’s Corner: Yours is the first case of a rapper I’ve talked to who said that they write the rhymes first, and then get the beat. And you think that’s where your style developed from? Because some of the rhythms you use are so crazy, and no other rapper is out there doing the same thing. You fit 5 syllables to a beat, or sometimes 6 to a beat.

Talib Kweli: That’s exactly it./ That’s exactly the inspiration. I had all these rhymes that were written a certain way. And then I would hear beats I would like, and I would literally try to fit them. You hear that and you read that as a severe criticism. You’re talking about it as something that’s interesting musically and I appreciate that. That’s something that’s been said about my style that people have said that they love and people say that they loathe. And for me, I’m glad that I learned that way. It makes my style unique. I feel like that’s what makes my style unique. I take comfort in something that Bob Dylan once said. He was like, ”When I go to a concert, I’m not going to sing along, or I’m not going because I can do what the artist on stage can do. I’m going to see them do something I can’t do. So when I go, I want to watch a virtuoso performance, per se.” And when he said that, it struck me. I was like, “Okay, that’s where I’m at artistically.” So while I still make music these days where I go in and out of that style, so sometimes I stay more static and rap to the beat when I’m really trying to get a point across. And then I go back into that. As opposed to earlier in my career, it was always like that, because I didn’t have any beats.

Composer’s Corner: So you have the line first, and then fit the rhythms to that line? You have the text first, and then you come up with the rhythms for it?

Talib Kweli: That’s how it started. Nowadays, it’s honestly married. I think about things in couplets. Rhymes pop in my head as I’m watching TV or walking down the street.

Composer’s Corner: So you’re constantly coming up with rhymes?

Talib Kweli: Yeah.

Composer’s Corner: The couplet form is far and away from the raps that you see earlier in your career. Did it take you a while to come back to this easier and simpler form to rap in? Do you start with the couplet and build off that?

Talib Kweli: Now, I come up with a bunch of couplets. And when they start making sense together, then I’ll write them down on my phone or piece of paper. Then it’s coming together. You know how you exercise a muscle and it becomes second nature? At this point creating music and getting the music from the stage of a thought in my head and to onto a record to onto a stage where I’m performing it, I see all of that at the same time now. When I was writing as a teenager at 13 or 14 years old, and this it what made my style develop, there was no outlet. There was no knowledge, there was no understanding of how anyone was gonna hear this. Now, I write with more experience, more resources, more urgency. Like, “Okay, I can get this out. I can shoot a video.” But back then, I was just writing for other writers only. I had a real interesting experience with Def Poetry Jam. My writing when I first started was intricate enough that I could go to a spoken word event and rap. And it people would take it the same as an ill spoken word piece. But when I got to do Def Poetry Jam by the time Black Star came out and Mos Def was a little famous and we could be on TV doing this, I froze up. Because I had been stuck in writing 16 bar raps for a couple years. And I had fallen out of the habit of being loose with the pen and writing these long, loquacious, multisyllabic rhymes. And I didn’t have anything that I felt like I could offer. And that’s sort of where “Lonely People” came from. The style that I rap on “Lonely People,” which is a record that I don’t think ever came out, thatr was like me trying to get back to that intricacy. That is a part of what I do.

Composer’s Corner: Early on, you didn’t have access to beats and styuff like thast. Some people, like you were saying before, would use that as a criticism. But you see that as something essential in the development of your personal, unique, signature style of loquaciousness?

Talib Kweli: Without a doubt. Of course there was the influence of my parents, how my parents raised me. They taught me what they taught me, and taking me to museums and libraries every weekend. That has had a huge impact on my style, my parents and the household that I came from in Brooklyn. But if we’re just talking technique, that’s where the technique comes from.

Composer’s Corner: Say you’re watching TV and coming up with couplets, like you were saying before, and you write it on your phone. When you come back to it later to work on that rap, how do you remember what the rhythm was in the first place? Do you write it down with spaces or slashes to indicate rhythms?

Talib Kweli: That’s what I was talking about, with the muscle memory. At this point, if I write it down, I can remember the rhythms.

Composer’s Corner: You’ve got such a complex style. Do sometimes consciously dial it back to make the message more straightforward for the listener?

Talib Kweli: Not so much to make the message. I never dial it back for the message, but I do dial it back for the musicality. Sometimes, it’s like Evidence, who’s a great producer-rapper, he said, “It’s not where you place your rhymes, it’s where you don’t.” Sometimes that’s true. Sometimes spaces are gorgeous. You need space, and you need time for the music to breathe.

Composer’s Corner: Can you think of the time when your style changed from not having the beats until after you write the rap to having the beats before you write the rap? It seems like you had that former style until at least through the debut Black Star album, Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star.

Talib Kweli: Definitely, definitely. John Forte was probably my biggest influence musically-wise, Hip Hop-wise. Here’s a guy from the neighborhood who knew all the rappers in the industry because he just went out a lot and was very ambitious. He was a very talented rapper back then. Me and him were kind of a group, partnered together. We never had no beats. And instead of waiting on people to give us beats, Jpohn Forte learned how to make beats. And to this day, his learning how to make beats and play the guitar has been his saving grace. It’s carried him through life. He learned how to make beats, so my first beats I got were from John Forte and people around him. You asked earlier who taught me how to count bars, it was John Forte. He was like, “You’re rapping too much, you have to count bars. This is where the hook goes. Songs have a format.” I didn’t know any of that. Me and him are the exact same age. We met freestyling in Washington Park. We both went to boarding schools. We graduated the same year. We became roommates at NYU. But when we became roommates at NYU, while I went to theatre school, he spent one week at NYU and went and said, “I’m going to do music for a living.” And he dropped out.

Composer’s Corner: That seems to be a theme with your crew. I think Jean Grae did the same thing, she dropped out of NYU after she realized she already knew everything about the music business that they were going to teach her.

Talib Kweli: Yeah. Do you know how far back I go with Jean?

Composer’s Corner: I think I found out about Jean through you, but didn’t realize it went back that far.

Talib Kweli: Well, I knew Jean before I knew John Forte. When I met Jean Grae I was 14-years old. She wasn’t rapping publicly. She was just Tsidi, the girl we used to hang out with in the village. Then she started rapping. I can’t say whether she just started rapping or if she just started rapping in public. But she was really, really, really, really extra good. Those rhyme ciphers I was talking about in Washington Park, she was there. She was there for all of that.

Composer’s Corner: So is it only recently that your relationship with her has become more professional? For instance, she was on your label, and you guys started showing up on each other’s songs.

Talib Kweli: Jean is like a real New York city kid. She wasn’t just into Hip Hop, she was into all the underground music that was coming out of New York at the time. There was a trance scene, and an electronic scene, and a rave scene, and house music. Jean was doing all of that, where I was just doing Hip Hop. Jean kind of disappeared off the scene for a minute around the time when I was hanging out with John Forte actually. Then she came back around. People started putting out independent records. There was this crib on Clinton in Brooklyn, in Clinton Hills, where it was like OT, and Aggie, and Bad Seed, and Jean Grae, and Pumpkinhead, and everybody would be at this one crib making music. And Jean was the break-out all of that. She was making tracks under the name Run Run Shaw . She had ill raps. The group was called Natural Resources, and they were performing all around the city. They were developing a buzz. Jean started developing a buzz actually before I started developing a buzz.

Composer’s Corner: I didn’t realize that. I always thought it was funny, that four of my top five rappers have close relationships with each other, both personally and professionally. That’s you, Jean, Pharoahe, and Mos Def. How did you get to know them?

Talib Kweli: When Jean started making records and popping off, and becoming Jean Grae, developing the style she’s with now, that’s when I was on Rawkus. So we were part of the same scene, but it was different crews. Years later, when my manager and I, Corey Smith, came with the idea of doing Black Smith Music, we started talking about artists. And the first artist I mentioned was Jean Grae. I didn’t know he was aware of Jean Grae. And not only was he aware of Jean Grae — as you know, she likes to go out to party and drink — but Jean was one of his drinking buddies. They would party together often. I kneow her from Washington Square park, and Hip Hop shit. And he knew her, like, “Oh, that’s the girl I hang out with all the time.” Me and Corey both were like, “Okay, yeah, Jean is perfect for blacksmith.” I had been trying to get Jean on a song. Jean Grae jumped on “Black Girl Pain”, but I had tried to get Jean on Black Star. She was just doing her own thing. But she jumped on “Black Girl Pain,” and me and Corey get the label, that’s when we were like, “Jean Grae.” So that developed into my real friendship with Jean. Me and Jean were really good friends when we were 14, 15, and then we didn’t hang out for years. And then we became close again, years later.

Composer’s Corner: A lot of discussion in Hip Hop is over flow: what it is, who has it, and stuff like that. If you had to define it, what would you say? And how do you create good flow?

Talib Kweli: Flow for Hip Hop is like improvisation for jazz. Everyone has a different style. You have Miles, you have John Coltrane, and they have their own signature horn style, and that’s what your flow is like. The beat can remain the same or the beat can change, but your flow is how you interpret the beat. For me, the more free and loose I am, the better I flow. It’s something that you can overdo, or it’s something that you can not pay attention to. My flow has developed over time. I personally feel like right now in my career, over the past 4 or 5 years, I’ve been flowing the best of my career. Definitely. I would argue anybody down and play records. I would say, “Listen to my flow on this. Listen to it.” I feel like I’m becoming a master of my style, and I’ve experimented with a lot of different flows. A lot of different ones.

Composer’s Corner: Is rap more poetry, melody, or is it when you combine both together?

Talib Kweli: It’s all of that. It’s definitely when you combine all of that together. There are rappers who I love, that I’m scared of, like, “Damn, that motherfucker can flow. Damn, he can rap.” But they’ve never made a song I like. I wouldn’t go as far to name them.

Composer’s Corner: You’re saying that it never came together, the flow working well with the beat?

Talib Kweli: Yeah. You hear somebody and you recognize the talent, and you’re like, “Wow, that person can really rap. Wow, if they could just figure out what beat to flow on and how to make a song, it would be dope.” I’m aware enough of myself as an artist to know that there’s people who feel that way about me. There’s people who feel like “Get By” is my only good song, and I don’t pick good beats. I would beg to differ. But there’s people who feel like that, and there’s people who feel like that about me as well.

Composer’s Corner: So does every rapper have their own unique flow? And the question is how to make it fit to a certain beat and how to express yourself in a way that makes sense?

Talib Kweli: I’m saying that’s how it should be, and that’s what the best rappers do. There are flows that get popular. There was a Jadakiss flow that got popular. You know whose flow has gotten extremely popular lately? Chief Keef. The whole industry started rapping like that. There’s certain flows that get popular and people run with them. Definitely, Das EFX had one of the more popular flows.

Composer’s Corner: You were saying you flow the best when you’re free with it. Do you mean with where your place your rhymes, how long your sentences are, the words you use, or stuff like that?

Talib Kweli: All of that, but also how relaxed it is. Even if it’s a loud beat and an aggressive rhyme, the more relaxed I am when I’m performing it, it just flows better. It melds into the track better.

Composer’s Corner: I can’t think of a real specific song where you go hype on some shit, like DMX would.

Talib Kweli: There’s records that are certainly louder. “Human Mic,” on my new album that just came out, called Prisoner of Conscious. “Feel the Rush,” from my album Quality. There’s certain records. “We Got The Beat.” But yeah, you’re right. I would actually like to do that more. With Idol Warship, my collaboration with Res, I got to do different things flow-wise and vocally that I would have hesitated to do on a solo project.

Composer’s Corner: If you were to give advice to a starting rapper on how to be a better rapper, what would you say?

Talib Kweli: I would say study the greats. Study those albums. Great art is a collage. There’s nothing wrong with taking a bit of Jay-Z, taking a bit of Nas, taking a bit of Scarface, taking a bit of Ice Cube, taking a bit of whoever. Then, find an artistic community. Try to find one that’s live in the flesh, but definitely find one online. Soundcloud, Tumblr, wherever. Find an artistic community of people you can bounce ideas off of. That you can go rap to, and they can kick a rhyme to you that’s better than your shit that makes you go, “Oh, I got to go back to the lab.”

Composer’s Corner: What are some of those great albums you would say to check out?

Talib Kweli: Definitely Reasonable Doubt or Illmatic. Those to me are the giants of cohesive albums with incredible flows and lyrics. There’s also Main Source’s album, Breaking Atoms. The early KRS-One album. With Boogie Down Productions, called BY All Means Necessary. The Blueprint. Those things are dope. A lot of the Nas albums. Nas albums definitely. Jay-Z albums. The Kendrick Lamar album that just came out, where as a lyricist you’re like, “Holy fuck.”

Composer’s Corner: Do you see anything knew on that album that could move rap in a new direction, with his flow or any of that?

Talib Kweli: What’s interesting about him is that he has a flow that is very much part of his crew’s flow. Sometimes I hear in Kendrick aspects of Ab-Soul, aspects of ScHoolboy Q, aspects of Jay Rock, and sometimes in their music I hear aspects of him. But everybody’s still got their own thing. And I like that. That’s what I mean about having an artistic community. When you hear them do a flow that’s similar, oit’s clear that it’s because thjey’ve spent a lot of time together. And everybody has their own interpretation of it. And that’s what makes them greta. Those guys lyrically man, you don’t find that since Wu-Tang, where lyrically everybody all have something to offer.

Composer’s Corner: Do you see that kind of mutual influence dynamic working in your crew at all, with Jean or Mos?

Talib Kweli: I consider myself part of a loose knit crew of the best emcees. I consider Black Thought as my crew. Jean Grae, Mos Def, Wordsworth and Punchline, I definitely consider that part of my crew and when you hear me on a record talking about my crew, that’s who I’m talking about.

Composer’s Corner: So kind of like the extended Okayplayer family.

Talib Kweli: Yeah, exactly.

Composer’s Corner: I want to see how your process of rapping works in real time. So I’m going to give you a line that someone else from your crew has rapped, and I want to see what you would do with it next, how you would continue that rap line. Is that cool?

Talib Kweli: Okay, let’s try that.

Composer’s Corner: This is a Pharoahe Monch line. I tried to pick a line that would be similar to what you’d write. I’ll read it, and you can say what rhythm you’d use, or how you’d rhyme next. The line is, “This line will remain in the mind of my foes forever in infamy.”

Talib Kweli: The first thing I would do is find a word, probably a multisyllabic word, that goes with infamy. Something as close to infamy as I could. That’s the first thing I’d do. “Symphony”, is probably the easiest one to pick. I’d think of what “symphony” has to do with that. I always approach it as a writer first. What would symphony have to do witht hat? I’d probably spend some time on it. Symphony…Then I’d say something like, “The words are my instruments, it’s a symphony.” That’s about three-fourths of a couplet, right there: “These lines will remain in the minds of my foes forever in infamy.” That’s most of it taken up, so I only got a little bit left. So my flow would be dependent on that. You know what I’d probably do right there? I’d probably save what I just came up with, “The words are my instruments, it’s a symphony,” and find another word that rhymes with it. Let’s say “mystery”, for the sake of argument. So it’d be, : “These lines will remain in the minds of my foes forever in infamy / They don’t have a clue, it’s a mystery / “The words are my instruments, it’s a symphony.” And maybe add, “When I’m on the mic, I make history.”

Composer’s Corner: That’s actually very similar to what Pharoahe Monch does with that line, which is from the song “No Mercy.” He raps, “This rhyme, will remain in the minds of my foes forever in infamy / The epitome of lyrical epiphanies / Skillfully placed home we carefully plan symphonies.” You can see that he also rhymes on symphony, and actually has the same rhythm for that first line.

Talib Kweli: Maybe that’s just me remembering what he did then, since I’ve heard it before.

Composer’s Corner: True. Let’s try just one more. How about, “Real rhymes, not your everyday hologram.”

Talib Kweli: I’d think about twitter, or instagram, or follow man, but toss that to the side because that’s too easy…I’d probably go with a metaphor about Kevin Bacon as the character Hollow Man from that movie. So something like, “Real rhymes, not your everyday hologram / Can’t see through it, Kevin Bacon, no Hollow Man.”

Composer’s Corner: Damn. Shit man! You can come up with that so quick. That’s what you were saying before, how you see it all. I think of a point guard who sees the whole court and sees stuff develop before anyone else doies.

Talib Kweli: Point guard is a great example. I grew up playing baseball. People say baseball is boring, but the reason people say boring is because the whole time you have to see every possible scenario. And I think that’s helped me in my writing.

Composer’s Corner: Sometimes, I’m not too hot on rappers who seem to write 2 lines and then skip to a different subject. They just seem to have not written one verse all the way through, and just throw together bars willy-nilly until it makes 16.

Talib Kweli: Well, there are some great non-sequitur rappers though. Ghostface, Killah, MF DOOM is probably the greatest. I think there’s a style to it. I think Lil Wayne, to be honest with you,a s very good at it. People get mad at home because he focuses strictly on eating pussy at this point. That’s what it is, it’s not that he can’t do it. But think of how many different ways he’s come up with to tell you that he likes eating pussy.

Composer’s Corner: That alone is impressive.

Talib Kweli: Yeah, pretty impressive. [Laughs]

Composer’s Corner: Actually, that second line I gave you to rap off of was an MF DOOM line, from the song “Vomitspit.” I picked those lines because they reminded me of something you might spit, with longer words and rhymes and stuff like that.

Composer’s Corner: Say you’re in the studio and you’re coming up with your line. How much of the rhythm at the mic when you’re recording is improvised or worked on? Or is it the same take every time?

Talib Kweli: I definitely try different flows. I definitely do, for most of my rhymes. Especially the morewordy ones. Some of them are just straightforward. But for the more wordy rhymes, I try different flows every time until I lock in on one that makes sense. And then I perfect that one.

Composer’s Corner: In the recording process, how much of there is a back and forth between the rap you come up with and the beat the producer has come up with?

Talib Kweli: Truthfully, every song is different. I would definitely say the majority of the time it’s me going through rough, rough beats. Rough soul ideas. Loops, and drum ideas, and stuff like that, and then I’m like, “I like that.” And then getting with the producer and we add stuff to it.

Composer’s Corner: So you’re in on the producing pretty early?

Talib Kweli: I’m in on the process of picking the track early, but producing is adding everything to it. I pick a lot of loops, I pick loops. Like, “Okay, I like that,” then we build on that. To me, the build on top of it is obvious.

Composer’s Corner: Jean Grae had a theory that certain words, and even certain syllables, elicit emotional responses in listeners. Do you feel the same? And do you have a favorite word, like she does?

Talib Kweli: I don’t know if I have a favorite word. I think she’s right, and that’s something that you have to know intuitively.